(formerly Kirchnerstraße 21)

by Anne Kupke

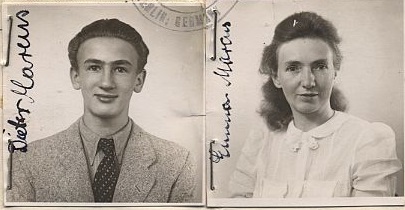

This article was published in German on the website of the Verein für erlebte Geschichte in Halle an der Saale. On 12 November 2024, Stolpersteine were laid at Kirchnerstrasse 17 to honour the family of Erich Marcus (1896), Siegfried Marcus, his wife, Emma (née Becker), and their three sons: Erich (1927), Dieter, and Peter.

See as well:

The Family of Emma (née Gassenheimer) and Simon Marcus

The Family of Samuel (1837-1892) and Lotte (née Stein) Gassenheimer

Descendants List of Samuel (1837-1892) and Lotte (née Stein) Gassenheimer

Mozartstrasse 24— The Family of Paul and Hertha (née Loeb) Marcus

Siegfried Marcus, his wife Emma Marcus and their three sons Erich, Dieter and Peter as well as Siegfried’s brother Erich Marcus once lived here.

The residential building at number 21 once stood on the left-hand side of the passageway from Kirchnerstraße to Halle’s main railway station. Around 1915, Emma and Simon Marcus moved into a spacious flat with eight rooms and a balcony on the second floor. From there, they had a direct view of what was then Thielenplatz. Today, the bus station is located on this site.

When Emma and Simon Marcus moved from Dessau to Halle, three of Emma Marcus’ siblings were already living in the city on the Saale: Georg Gassenheimer with his wife Selma and daughter Ruth, Minna Frankenberg with her husband Nathan (->STOLPERSTEINE Feuerbachstraße 74) and Elise Ney (->STOLPERSTEINE Maybachstraße 2).

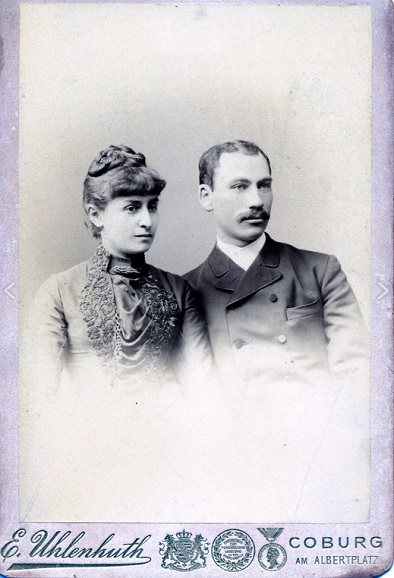

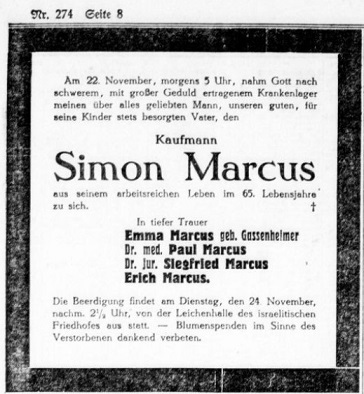

Emma Marcus (*1864) was a born Gassenheimer. The large Gassenheimer family came from Themar in Thuringia and specialised in the manufacture and sale of agricultural machinery. Simon Marcus (*1861) was a merchant and joined the business.

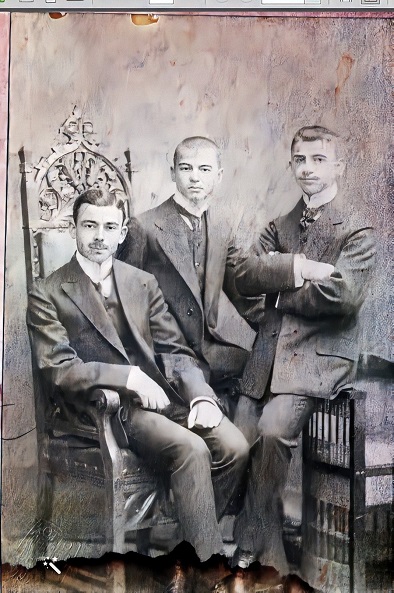

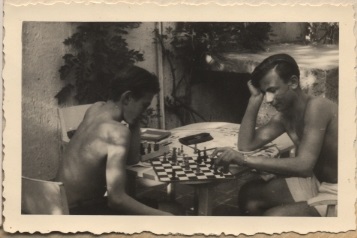

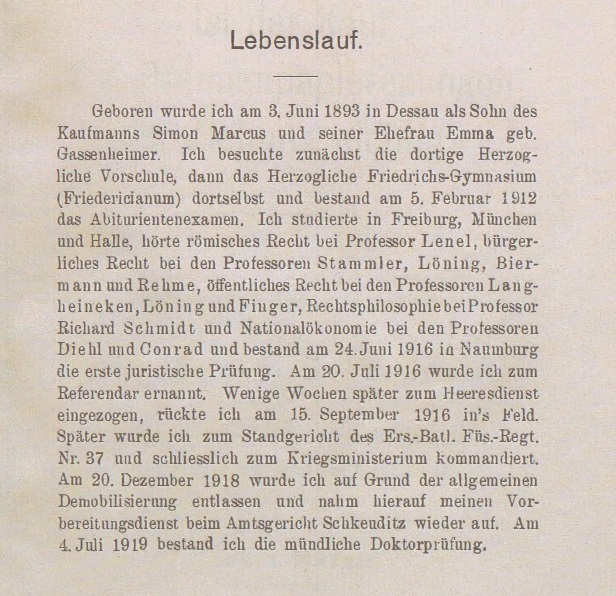

The couple had three sons: Paul (*6.2.1891), Siegfried (*3.6.1893) and Erich (*4.3.1896). All three were born in Dessau and had also attended school there, the Herzogliche Friedrichs-Gymnasium. Paul began studying in Munich, Siegfried followed his brother and decided to study law. Both joined a Jewish student fraternity there. Siegfried then went to university in Freiburg and on to Halle. Erich was to become a businessman and join the Gassenheimer business.

The First World War broke out in 1914. Siegfried Marcus initially continued his studies, passed his first legal examination in Naumburg in the summer of 1916 and was appointed a trainee lawyer. From September 1916, he served in the army in a legal capacity, first at a court martial and later at the Ministry of War. All three Marcus brothers had volunteered to go to war for Germany.

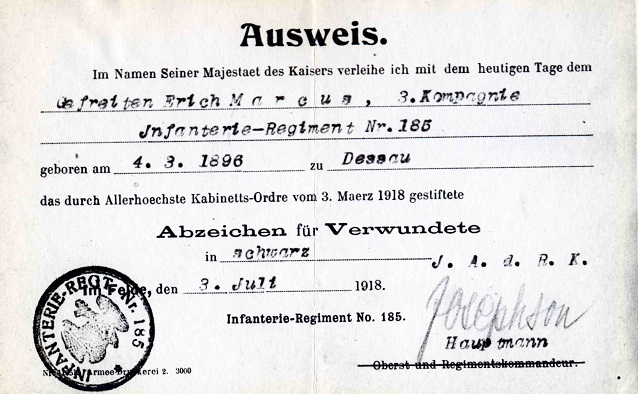

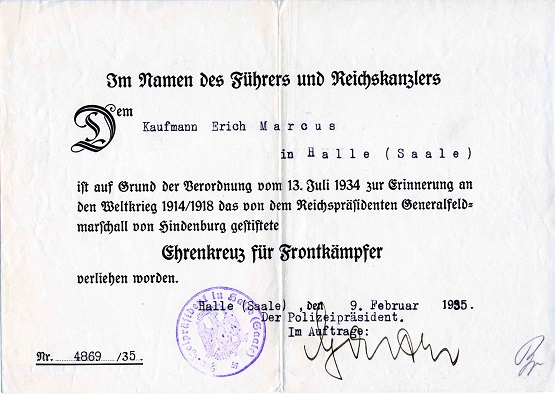

Siegfried Marcus even concealed his glass eye, which he had had since childhood due to a splinter in his eye. Paul Marcus served as a field doctor. Erich Marcus was buried during an attack, suffered gas poisoning and was treated in a Belgian military hospital for a long time. He was awarded the Wounded Badge and the Cross of Honour for Frontline Combatants.

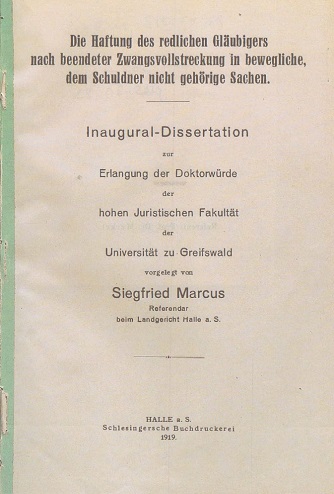

All three Marcus brothers returned to Halle from the war at the end of 1918 and lived with their parents in Kirchnerstraße. Siegfried took up his traineeship at the local court in Schkeuditz, became a trainee lawyer at the district court in Halle and submitted his dissertation to the University of Greifswald in 1919. He was a member of the “Barmherziger Brüderverein Halle”, the liberal “Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens” and, like his brothers, the “Jüdischer Frontkämpferbund des Bezirks Halle”. All of these associations were banned in 1938/39.

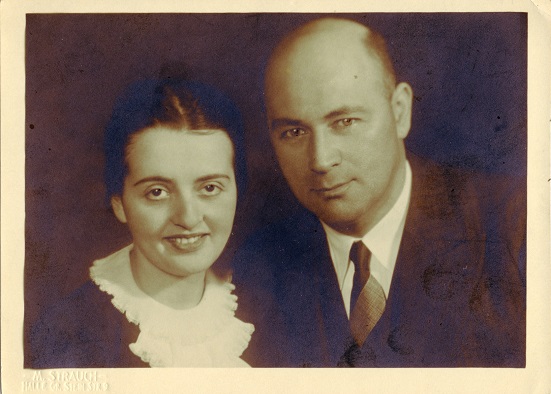

Siegfried Marcus opened his own law firm in 1923. He was initially based at Große Ulrichstraße 57, but after a year he moved to offices at Am Steintor 18, where he met Martha Emma Becker. Emmi, as she was usually called, came from a working-class family and lived with her parents at Hedwigstraße 21, around the corner from Siegfried’s office. She had four younger siblings: Martha, Lisa, Friedel and Walter. There was an undertaker in the house, where her mother worked lining coffins. Emma had already helped with this work as a child and later began working there too, until she started working in a sausage factory.

The Beckers were Protestants, but not particularly religious, just like Siegfried Marcus, who came from a Jewish family, but for whom religion played no role in everyday life.

Emmi and Siegfried fell in love with each other. However, Siegfried’s mother, whose father had already died in 1925, was firmly against marrying the young woman from a humble background, who had the same first name as herself. Emma Marcus, who had enabled her sons to study and pursue a professional career, presumably hoped that her son would be a suitable match, but Siegfried stood by Emmi and promised to marry her at a later date.

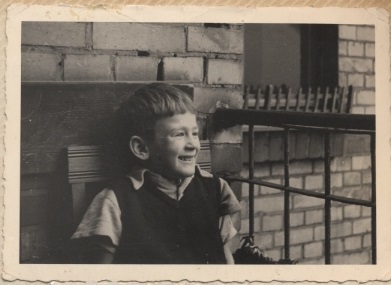

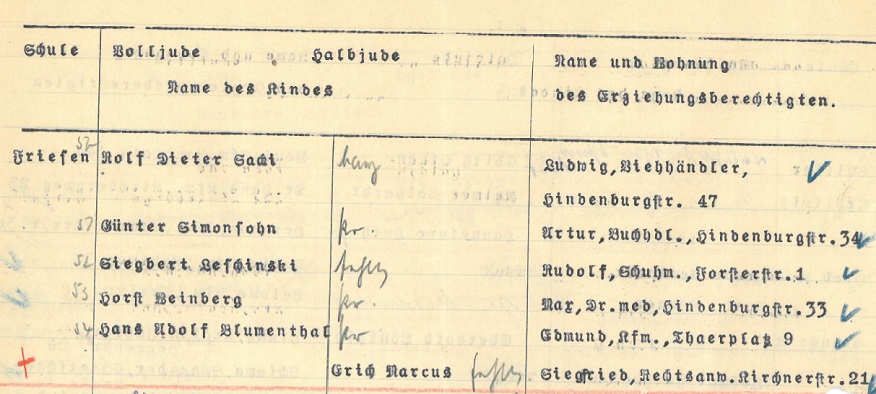

Then the first two sons were born: Erich (*1 June 1927) and Dieter (*21 May 1932). Both lived with their mother in Hedwigstraße with Emma’s mother and Emma’s younger siblings. Emma’s father had not returned from World War I. Siegfried Marcus often came to visit and helped where he could, but lived with his mother in Kirchnerstraße. His brother Paul and his brother Erich also lived here until Paul’s marriage to Hertha Loeb in 1927. When Erich married Karola Mendel (*12.8.1907-2002) in 1931, he also moved out of the parental home and set up his own household with his wife at Brucknerstraße 11. Erich worked as a salesman for agricultural and household machinery. He travelled around the countryside by car, delivering appliances from Gassenheimer and other companies, such as “Miele”, to rural customers.

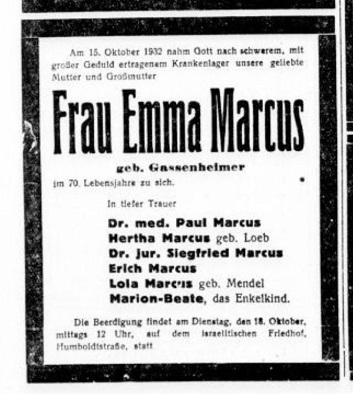

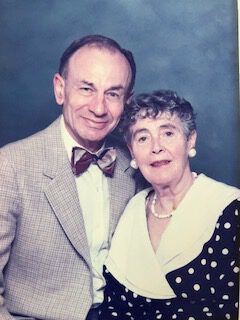

Despite her disapproval of her son’s marriage, Emma Marcus took a keen interest in her grandchildren’s upbringing. She learnt their names and watched her mother and children at least once from a café that Emma Becker regularly passed with her pram. Emma Marcus died in 1932 at the age of 70. Siegfried kept his word and they married shortly afterwards. The family of four moved into the parental home in Kirchnerstrasse. In 1936, their third son, Peter, was born.

Siegfried Marcus had read the book “Mein Kampf” and felt it was safer not to have his sons circumcised or raised Jewish, even though his wife had been willing to convert to the Jewish faith.

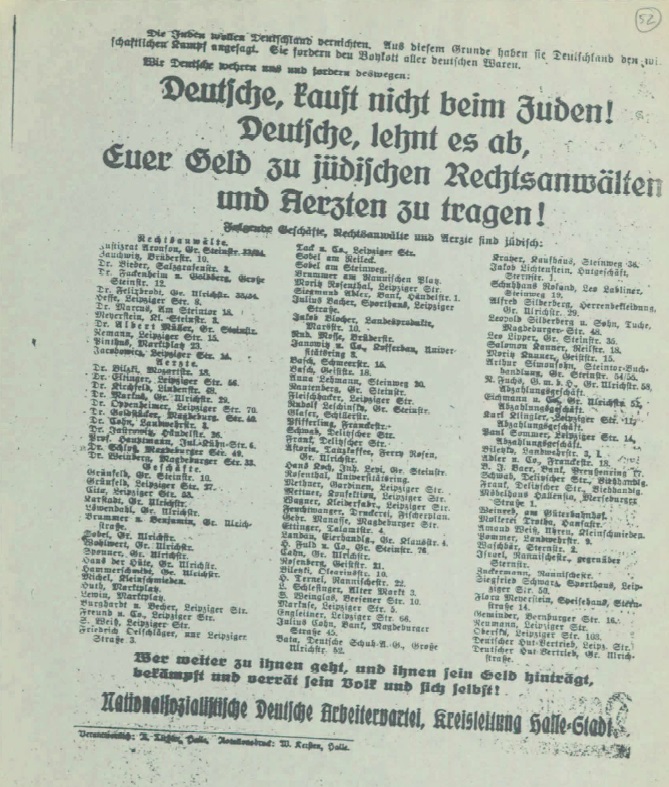

When the National Socialists came to power in January 1933, one of their first measures was to oust Jews from certain offices and professions. As early as April 1933, a law was passed that revoked the licences of Jewish lawyers. However, the law made an exception for former lawyers who had been admitted to the bar until 1914 and those who had served on the front in the Great War, which applied to Siegfried Marcus. At the beginning of 1933, 13 of the 104 lawyers and notaries in Halle were of Jewish origin. By December, there were only five left. Their names and addresses appeared at the top of the leaflet calling for a boycott of Jewish lawyers, doctors and business people in Halle in April 1933. Jewish lawyers in Halle were forbidden to stay in the lawyer’s office, where everyone had a personal locker. From now on, they had to bring their robes with them in their briefcase.

Siegfried Marcus was initially able to continue working as a lawyer, but the measures already taken by the National Socialists against all Jews and those yet to be announced became increasingly massive and directly affected the Marcus family in 1938:

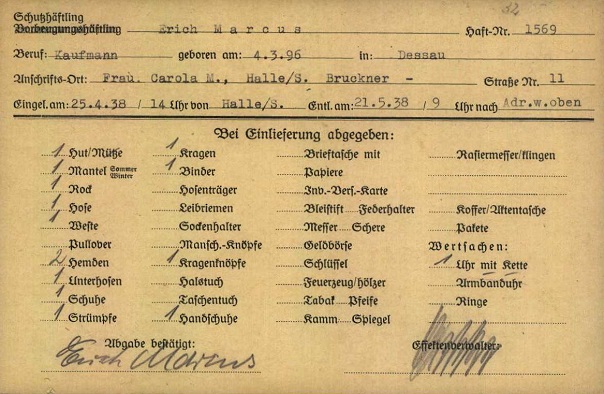

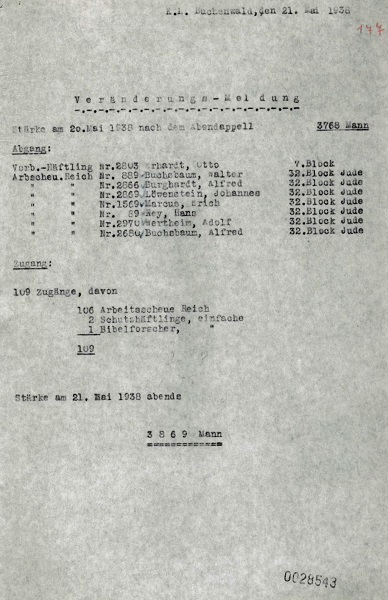

On 25 April 1938, Erich Marcus, Siegfried’s brother, was arrested and taken to Buchenwald concentration camp. During the transport, he met his cousin Hans Ney and other Halle residents such as Leopold Nussbaum and Julius Pfifferling, who were housed in the same block. The arrest took place in connection with the “Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich”, in which around 10,000 men were sent to concentration camps in several waves in 1938, including an above-average number of Jews. Ostensibly, the preventative arrest of people with criminal records and “asocial” behaviour was intended to reduce criminality. In the case of Erich Marcus and many others, the real aim was apparently to try to get people to emigrate in order to seize their assets.

Erich Marcus was released on 21 May 1938 with the verbal order to leave the country quickly. He complied and applied for a visa for the USA for himself and his wife. He liquidated his company “Erich Marcus, Maschinen für Land- und Hauswirtschaft”, which had existed since 1923, in order to pay the Reich Flight Tax of 20,000 Reichsmark (RM) and other taxes, which meant that most of the emigrants left the country almost penniless. At around the same time, Erich and his wife Karola were expelled from their flat at Brucknerstraße 11 and found refuge with Karola’s family at Landwehrstraße 23.

Siegfried and Erich’s older brother, the doctor Paul Marcus (-> STOLPERSTEIN Mozartstraße 24), was preparing to emigrate to Uruguay at this time. He left Halle with his wife and child in September 1938.

It was now announced that the exceptions for front-line fighters among Jewish lawyers would be cancelled in September 1938 and only individual “Jewish consultants”, as they were now called, would be permitted. These were only allowed to represent Jewish citizens.

Another event ultimately led to Siegfried Marcus’ escape from Germany. In the late summer of 1938, he was summoned to the police building on Hallmarkt. He took the Iron Cross with him to the interrogation, which he had received for his service as a front-line fighter and with which he wanted to prove his loyalty to Germany. There he learnt that offering a cigar to a fellow player at skat in the pub would be interpreted as a bribe to a judicial officer. The other player was a bailiff. The Iron Cross did not help Siegfried Marcus, it was knocked out of his hand and he was taken to a cell. Siegfried Marcus suspected that the real reason for his arrest was a case he had brought on behalf of a Jewish businessman who had been expropriated.

It took Emma Marcus several days to find out where her husband was.

What happened next was passed on in the family as follows: her husband asked her to go to Berlin and visit a friend from their time together in the military, who had since gained a higher position and was a member of the NSDAP.

Emma Marcus found him in Berlin. He arranged for his friend’s release, but warned her that Siegfried would already be at home when she arrived back in Halle. He should flee immediately, however, as they would soon realise that the release had been a mistake. And so it happened. Emma Marcus found her husband when she returned home. They hurriedly packed a suitcase and left the flat. They no longer dared to go to the bank to withdraw some money. Aunt Friedel, Emma’s sister, stayed with her sons Erich (11), Dieter (6) and Peter (2), who looked after their parents from the window until they disappeared into the railway station.

Emma accompanied her husband to Rotterdam and then returned to the children. Siegfried Marcus paid for the ship passage to New York and, because he only had a visitor’s visa, also for the return journey, with the actual intention of staying in the USA for the time being.

In the time that followed, Emma Marcus was visited several times by the Gestapo, summoned and questioned about her husband’s whereabouts. She answered truthfully that she did not know when he would return. During these conversations, she was vehemently pressurised to divorce her Jewish husband. She repeatedly refused and stood by her husband, despite the consequences for her and her children.

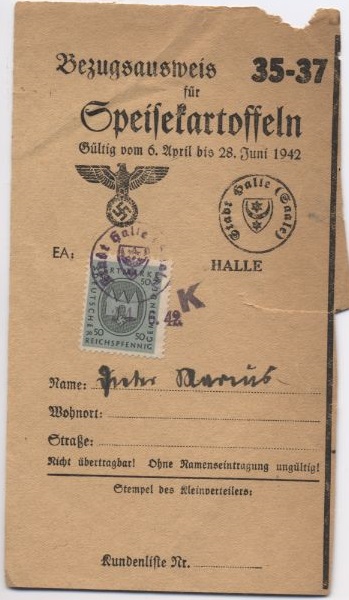

Emma Marcus was now more or less destitute with three small children. Her siblings, with whom she had close contact, tried to help, but had hardly any money themselves. Without a divorce, Emma Marcus received no work book and without a work book she received no work. Although her husband’s assets were initially transferred to her, they were then declared “forfeited to the Reich”. After a hard struggle, the bank paid her quarterly amounts of between 250 and 350 RM from the remaining securities. However, she had to pay RM 135 a month for rent and RM 40 for school fees, which was twice as much for Jewish “mixed-race children” as for non-Jewish children. Three times she was refused payment altogether because she did not agree to the divorce. Out of necessity, Emma Marcus began to rent out three rooms of her large flat in Kirchnerstraße, whereby she was told to only take in foreigners. Among others, a Swedish actor from the municipal theatre and a Czech who worked as a waiter in Halle lived with her. The family had so little money that they were often not even able to redeem the food stamps they were entitled to, which were less than those of the “Aryan” population. The middle son, Dieter Marcus, remembers hunger as a constant companion during these years.

Dieter often slipped under the barrier onto the platforms of the main station, which at that time could only be entered with a platform ticket. There he took on small jobs for travellers who didn’t want to leave the waiting train during a stop, fetching a newspaper, a drink or sometimes carrying a suitcase. He was eyed suspiciously by the professional suitcase carriers. He was often allowed to keep the change and proudly brought it home to his mother, who praised him for contributing so diligently to the family income. While Dieter spent many afternoons at the railway station, he also saw deportation trains passing through Halle or even stopping here. People would often shout out something, e.g. names, but you couldn’t get near the trains. They were guarded.

Emma Marcus lost her home around 1942. The landlord evicted her and the children. The case was heard in court, and her marriage to a Jew was ruled against her in the second instance. Emma Marcus found a small three-room flat at Huttenstraße 83, where the four of them spent the first six weeks sleeping on the floor in coats. Moving vans were not available, most of them had been confiscated by the Wehrmacht. The owner of the house there had stored the extensive household effects from Kirchnerstraße in the attic and demanded 400 RM as compensation, a large sum at the time. After the belongings from the large 8-room flat in Kirchnerstraße had been brought in, the family lived in extremely cramped conditions in the new flat.

According to the regulations at the time, Erich, Dieter and Peter were considered “half-Jews” and their parents’ marriage was considered a “privileged mixed marriage”. The fact that the children were not raised Jewish and the father had left was interpreted in their favour by the authorities. Nevertheless, the children suffered numerous forms of ostracism: Dieter remembers verbal abuse and physical attacks from children in the neighbourhood, but also friendships that withstood the social pressure. For example with Werner Koch, who had a communist father. Erich, who attended Friedrich-Nietzsche-Schule, Oberschule für Jungen (now Hans-Dietrich-Genscher-Gymnasium), was very close friends with his classmate Hans-Dietrich Genscher. His friend’s Jewish background played no role for him. He visited the Marcus family in Kirchnerstrasse and welcomed Erich into his home.

Emma’s sons were also told by the police that they were not allowed to have relationships with non-Jewish girls. The mother protested, pointing to the boys’ young age. The police replied that the instruction was mandatory.

In 1942, Erich had to leave grammar school at the age of 15 and, despite good grades, was unable to take his Abitur as planned. His mother resisted an apprenticeship as a bricklayer or carpenter, which the labour office had planned for him, citing Erich’s good grades. She eventually placed him in the laboratory of the Nietleben cement works. After about a year, in May 1944, he was picked up by the Gestapo and put on a train to Normandy. This affected many men who lived in mixed marriages, “half-Jews”, “unworthy of defence” criminals and “gypsies”, who were now assigned to the work battalions of the Organisation Todt for forced labour. Erich Marcus was in a camp in Mantes from 10.5.1944 to 30.9.1944. In the region north-west of Paris, he had to maintain destroyed railway lines as a railway labourer. The work was hard and dangerous. As a rule, labourers worked 12 hours a day with poor rations and long walks to the work sites. The forced labourers wore wood-soled shoes and light-coloured drill overalls, which were particularly visible to the Allied pilots during the constant low-flying raids after the invasion of Normandy.

In the confusion of the Allied advance, many prisoners took advantage of situations such as air raids to escape. Erich Marcus did the same. Because he was on his way to a new location during one of these attacks, he had his suitcase full of civilian clothes with him. This enabled him to make his way to Halle unrecognised. Here, however, he was recognised on the street and denounced.Together with 15 other men and boys, including two 14-year-olds, the then 17-year-old Erich Marcus was taken to the Sitzendorf labour and education camp in Thuringia on 1 November 1944. The accommodation, initially without water, light or beds, was in a disused porcelain factory in Unterweißbach, two kilometres away. There were around 200 prisoners in the camp, mainly “Jewish half-breeds”, but also Poles, Russians, French and Italians. The men, who came from very different professions or had been schoolchildren until shortly before, now had to do hard physical labour for the Troma works. Their main task was to construct buildings that were to be used for the manufacture of catalysts for the production of special aviation fuels. During this period, from the summer of 1944, numerous such projects were started in the centre of the country, in remote valleys and tunnels.

At the beginning of April 1945, the Americans approached Thuringia. The German guards gradually left the camp without authorisation. In this situation, Erich Marcus escaped and spent the last days of the war hiding with his mother at Huttenstraße 83. From this time onwards, he suffered from a nervous disorder that stayed with him until the end of his life. Erich never spoke to his family about his time in Normandy and Sitzendorf.

Meanwhile, Siegfried Marcus had made every effort to gain a foothold in New York. He sold his return ticket to Rotterdam. The proceeds were his starting capital. Initially, he bought household goods such as razor blades, shoe polish and shoelaces, rang the doorbells of strangers and sold the items out of a suitcase, at a slightly higher price than he had bought them himself. As he couldn’t get an official work permit with his visitor’s visa, he took on other jobs, such as a delivery boy. He rented a single room in a flat block. When his brother Erich and his wife Karola came to New York in April 1939, they even lived there together for a while. When his visit visa expired after being extended several times, Siegfried Marcus had to leave the USA. He travelled to Havana, Cuba, from where he was able to enter the USA legally, but as a stateless person, in April 1941. The German Reich had expatriated him in the meantime, and now he also received a work permit and found legal work at the Jumbo Store in the Bronx, where he cashed in and priced goods. He later became a partner here.

He told his children about the Jumbo Store, which had a large elephant on the roof, on a postcard to Halle, before the USA’s entry into the war in December 1941 meant that direct postal communication between the two countries was no longer possible. Meanwhile, his brother Erich Marcus worked as a chauffeur and butler, Karola as a maid for a wealthy family in New York State.

In May 1945, the war was finally over. During the brief occupation of the American troops from April to early July 1945, 13-year-old Dieter Marcus met an American soldier in Halle who came from the Bronx in New York and happened to know the elephant business. The soldier wrote to his wife in New York, who visited the shop and promptly met Siegfried Marcus. This re-established contact between the family members and Emma received financial support from the newly founded Jewish Restitution Organisation from January 1946. She and her sons were also recognised as “victims of fascism”. The assets that the family had owned until 1938 were nevertheless irretrievably lost.

In June 1946, Emma Marcus and her three sons were allocated a flat in a large house with a garden at Kiefernweg 3a, very close to Heiderand. The family lived here for about a year. After that, this and other houses in Kiefernweg were made available to command personnel of the Soviet Army and the Marcus family moved to Heinrich-Heine-Straße 8 in September 1947.

The Soviet authorities offered Siegfried Marcus, via his wife, that he should come back and could become Minister of Justice here. However, Siegfried Marcus did not want to come to the Soviet zone for political reasons. His family was supposed to join him in the USA, but the authorities did not allow this. So Emma gradually sold off parts of the household in secret and used the proceeds to pay a lorry driver to smuggle her and the children across the border to West Berlin in an adventurous journey. From Bremen, Emma and her sons boarded a ship to New York in March 1948 with financial help from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS).

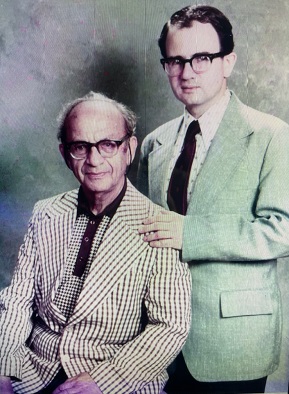

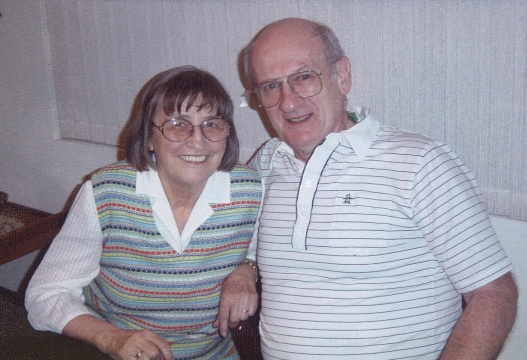

The now reunited family moved into a shared flat here. They tried to overcome the long period of separation and reconnect, which ultimately worked out well. Initially, Siegfried’s brother Erich lived with the family. His marriage to Karola had broken down in 1946. Erich Marcus died in New York in March 1975, Emma Marcus lived until 1974 and her husband Siegfried Marcus died in 1979.

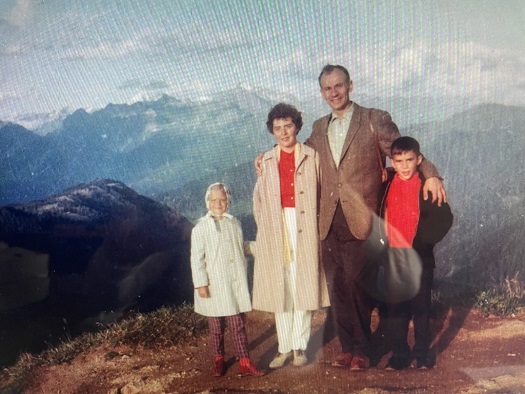

The children of Emma and Siegfried Marcus built their own lives in the USA. Erich Marcus became a doctor of chemistry and a respected researcher. He married Jutta from Halle, whom he had met shortly after the war and who had moved to the USA for him. The couple had two children, who had since grown up. Erich lived in Charleston, West Virginia, until his death in 1998. Dieter Marcus graduated in electrical engineering and did two years of military service for the US Army in Göppingen. During this time, he met the German doctor Christa Werner, who became his wife. He lives in San Diego/California, researches the family history and keeps in touch with all family members. Peter Marcus successfully developed crystals that are needed for digital watches and technical instruments. He lives in New York.

Sources and further information:

Descendants of Siegfried and Emma Marcus, especially Dieter Marcus

Stadtarchiv Halle, especially the Goeseke estate

Archiv Centrum Judaicum Berlin

Arolsen Archives

For more information on the history of the Gassenheimer family, see https://judeninthemar.org/de/die-familie-samuel-und-lotte-geb-stein-gassenheimer/ – a project by Canadian researcher Sharon Meen.

Georg Prick: Lawyer without justice. Persecuted lawyers of Jewish origin in the Higher Regional Court district of Naumburg during National Socialism. Published by the Saxony-Anhalt Bar Association.

Greifswald University Library, dissertation by Dr Siegfried Marcus: Die Haftung des redlichen Gläubigers nach beendeter Zwangsvollstreckung in bewegliche, dem Schuldner nicht gehörige Sachen. University of Greifswald 1919, printed by Schlesingersche Buchdruckerei Halle

From 1938, the University of Greifswald stripped Jewish doctors of their academic doctorates or honorary degrees. In 2000, they were posthumously restored, including Dr Siegfried Marcus, more information here https://www.uni-greifswald.de/universitaet/geschichte/universitaet-im-nationalsozialismus/rehabilitiert/

– Wolfgang Tarnowski: As a half-Jew in Nazi Germany. In: Ingrid Lewek and Wolfgang Tarnowski: Jews in Radebeul. Radebeul 2008. p.65-67. Available here: https://d-nb.info/1277270929/34

– Klaus Ulrich Rabe: “That is my credo: to do everything I can to prevent this from happening again.”. In: “Ask us, we are the last”. Published by the Berlin VVN-BdA. Part 4. p.36-46. Available at: https://berlin.vvn-bda.de/fragt-uns-wir-sind-die-letzten/

Private archive Joachim Kränkel in Sitzendorf

A short extract from a contemporary witness report by Dieter Marcus can be seen in: Letzte Zuflucht Villa Schloß.

A film by Mathilde Kowalski, Juliane Radtke, Susanne Siegert as part of the Multimedia and Authorship programme at Martin Luther University Nieuw Amsterdam: The ship on which Siegfried Marcus escaped to the USA https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nieuw_Amsterdam_(Schiff,_1938)