The family of Hugo and Eva Friedmann (née Kahn) played an important supporting role in the Jewish community of Themar in the first decade of the twentieth century. Hugo was the religious Lehrer/teacher of a community that was growing and prosperous. From its establishment in the early 1860s, the Jewish population of Themar numbered over 100 at the turn of the 20th century, and the Friedmanns were key to its religious and cultural traditions.

Eva Kahn was born in 1877 in Medernach, Luxembourg to German Jewish parents from the small villages of Wawern and Bosen. Kahns, who for the most part were cattle dealers, had been part of the texture of the small town of Medernach since the mid-1800s. Eva was the eldest of nine (9) children born to Nathan Kahn and his two wives, Sara Levi (1855-1889) and Mathilde Kahn (1863-1921). At least two of Eva’s siblings — Louis (1883-1885) and Cecile (1886-1886) — died at an early age, and it is possible that Theresa, b. 1883, and Hermann, b. 1885, did as well.

(For more information about Eva Kahn’s family, see: Eva Friedmann, and Descendants List of Berman & Rosa (née Hertz) Kahn.)

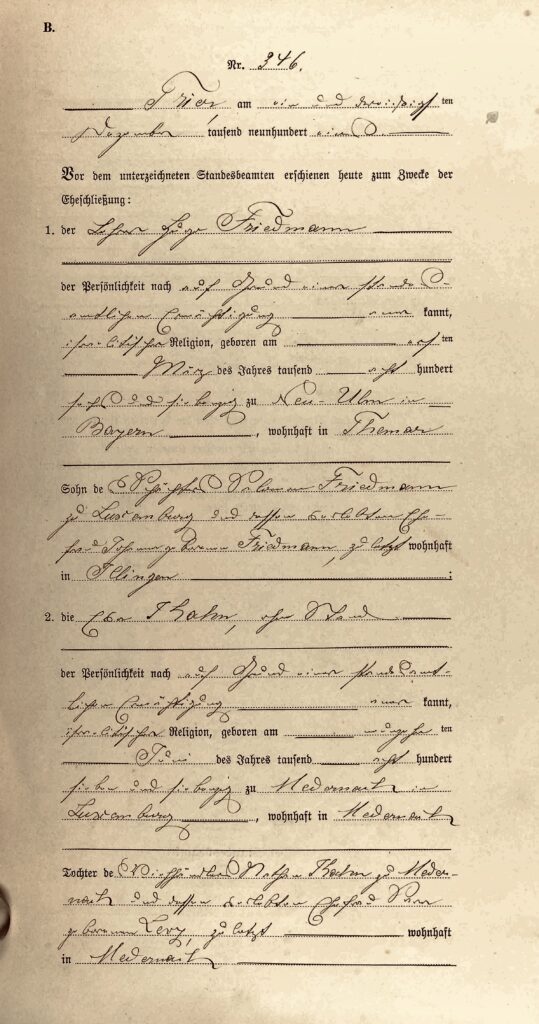

Hugo Friedmann was born in 1876, the fifth child of Salomon, a Jewish Lehrer/teacher, and Johanna; his immediate family included two sisters, Klothilde and Adèle, and one brother, Adolf; just two months before Hugo’s birth, Louis, one-year old, had died. While Hugo was born in Neu-Ulm, Bavaria, a city of some 9,000 people, he probably grew up in Illingen/Kreis Neunkirchen, Saarland, where his father was Lehrer from 1885 until 1895. (For more detail about Hugo Friedmann’s family, please see: Hugo Friedmann, and Descendants List of Salomon & Johanna Friedmann.

Hugo followed his father’s profession and, on 1 October 1892, started study at the Königliche Schullehrerbildungsseminar in Würzburg, completing his Lehrer/teacher’s certificate in July 1895. He returned to Illingen for his first posting but a year later received a posting in Schweich in the Mosel Valley, which had a Jewish community of about 90. Here his duties were those of Lehrer, Kantor & Schochet [ritual butcher]. Initially he taught 17 Jewish students, but this number increased to 20 in 1897, 15 girls and 5 boys. According to Kortel, while Friedmann’s work “earned the school an excellent reputation, the District Inspector considered ‘Friedmann still something of an apprentice whose skills required further development.’ In April 1898, Hugo left Schweich and moved on to Wetzlar.”

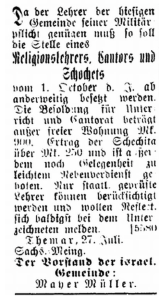

We believe that Hugo came to Themar on 1 October 1900 to fill the position of “Jewish Religious Teacher, Cantor, and Schochet” advertised in the 27 July 1900 edition of The Israelite newspaper: “Since the present Lehrer must leave the community to do his military service,” the ad read, “we are looking for someone to be Lehrer, Kantor, and Schochet. In addition to room & board, the salary as Lehrer and Kantor is 900 marks. Payment for ritual slaughtering is about 250 marks and opportunities for further income is possible. Only state-certified teachers can be considered and we ask that candidates submit their applications as soon as possible.”

Hugo and Eva Kahn married on 31 December 1901 in Trier, and she joined him in Themar, becoming a German citizen upon her marriage. Their first child, Johanna, was born at the end of 1902. Bruno, their youngest child, was born in Themar on 15 October 1908.

Themar was a thriving, bustling place during this time, growing from 1,782 residents in 1885 to 2,756 in 1905. The Jewish community was part of this growth — the Jewish Geburtsregister/Birth Register recorded 50 births between 1885 and 1900, although not all newborns survived infancy.

The Friedmann family lived at Oberstadtstraße/Hildburghäuserstraße 17, in the

living quarters at the synagogue and Jewish school. The lives of Hugo and Eva would have been busy with the upbringing of four children under age 10, the education of children in Themar’s public school, the religious education of the Jewish children in Themar and in Marisfeld, and the ritual slaughtering required for a community of approximately 100 Jews in Themar and 30 Jews in Marisfeld.

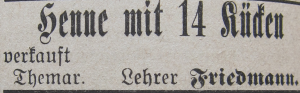

Few traces remain of the Friedmann’s time in Themar, but a search of the Themar newspapers yielded this ad placed in 1905: “For Sale: One hen with 14 Chicks, Lehrer Friedmann.” No address needed!

*****

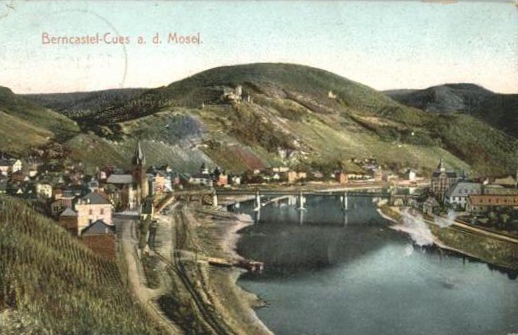

In 1909, Hugo Friedmann accepted a position in Berncastel-Cues in the Mosel Valley. On his departure, the Jewish Gemeinde of Themar presented him with a Krug engraved with the words, “To remember his congregation in Themar.”

Berncastel-Cues, a small city of about 4500 residents, lay 91 km. east of the German-Luxembourg border. Hugo and Eva were therefore closer to family: Hugo’s eldest sister, Klothilde, lived in Luxembourg City with her husband, Arthur Wolff, and their two children, Johanna/Jeanne and Léon. Hugo’s younger brother, Karl, either already lived in Luxembourg or moved there shortly afterwards; Richard, the son of Karl and his second wife, Friede, was born in Luxembourg in 1912. Adèle Friedmann lived in Brussels with her husband, Maurice Kouperman; they a son, Henri Richard, and daughter, Olga. Eva was also closer to her family: her father, Nathan, lived in Medernach, and her 30-year-old brother, Emile, worked in the mines; her stepbrothers were still young: Albert was fourteen, Otto just eight.

Berncastel-Cues was both similar and dissimilar to Themar: on one hand, Hugo was responsible for various Jewish congregations in small villages north on the Mosel: Lösnich (1909=28 Jews), Rachtig (1929=34 Jews), Zeltingen (1924=25 Jews). On the other hand, the Jewish population of Berncastel-Cues showed more advanced signs than did Themar of the population decline affecting provincial Jewish communities, as Jews either migrated to larger urban centres in Germany or emigrated from Germany altogether. The Berncastel-Cues congregation, which had peaked in 1866 at 110, numbered 82 in 1909.

In Berncastel-Cues, the Friedmanns lived in the synagogue building at Burgstraße 7. The four children grew to adulthood: in the mid-1920s, Johanna, the eldest child, married Karl Lang of Frankfurt am Main and moved there to live. The couple had two children, Wilma and Werner, in the mid-1920s.

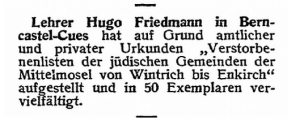

Hugo Friedmann published several books in the 1920s, among which was a 1927 Festschrift zur Feier des 75 jährigen Bestehens der Synagoge in Berncastel-Cues: Jüdische Gemeinde in Berncastel-Cues: ein geschichtlicher Rückblick/The Jewish Congregation in Berncastel-Cues: an historical Review to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of the Bernkastel-Kues synagogue. In 1929, he published the Verstorbenenlisten der jüdischen Gemeinden der Mittelmosel von Wintrich bis Enkirch, Bernkastel-Cues/A Listing of the Dead Jews of the Congregations of the Middle Mosel Region from Winterish to Enrich, Bernkastel-Cues.

*****

When the Nazi Regime began in January 1933, the Friedmanns were all in Germany. Hugo and Eva lived in Bernkastel-Cues (as it was now spelled; see note below), where the Jewish community had declined to 59, and Hugo had only two children to teach. The Langs lived in Frankfurt-Niederrad. Sitta lived with her parents until her marriage in December 1934 to Ernst Lewin, b. 1895, a businessman in Falkenburg with a distinguished WWI record. She then moved to his hometown of Falkenburg, a small city of about 8,600 people in Pomerania in northeastern Germany; in October 1935, Sitta and Ernst had a son, Joachim.

The family was clearly aware of the implications of the Nazis coming to power. Friedrich was the first to leave, emigrating in 1933 from Germany to Brussels to stay with his aunt, Adèle Kouperman (née Friedmann), and work in the Kouperman business. Three years later, Johanna, the oldest, and Bruno, the youngest, left Germany for South Africa. Johanna left first with her family. Bruno followed several months later — coincidentally, his future wife, Vera Marcus, b. 1912 in Pirmasens, also sailed on the Stuttgart, although they did not actually meet on the ship! “My mother, Vera,” her daughter tells us, “travelled with her parents, Hugo and Flora Marcus, and brother Paul Marcus to S.A. on the Stuttgart. My mother’s parents owned a shoe factory in Pirmasens and had gathered wealth which, I think, helped bribe many Nazis for their freedom.”

By July 1938, at the latest, Hugo and Eva made plans to leave Germany for Luxembourg; there were only 13 other Jews still in Bernkastel-Cues and all were seeking to escape. Nationality complicated the process: on 4 July, Hugo’s brother Karl, a widower since 1934, requested authorization for his brother and sister-in-law to enter Luxembourg on a ten-day temporary permit. The intent of course was that, once Hugo and Eva entered Luxembourg, they would not return to Germany. A Gendarmerie investigation on 7 July confirmed that some funds were available to support Hugo and Eva — Hugo had a bank account in Luxembourg — but, as his grandson writes, the amount deposited was “obviously not sufficient for staying 1000 years in the country (as the little moustached man was shouting everywhere his Reich will last as long).” Karl Friedmann was then asked if he would provide financial guarantees for his brother and sister-in-law; when he agreed, the local authorities authorized the 10-day temporary permit. On 10 October 1938 — a month before the Reichspogromnacht destroyed the synagogue where they had spent thirty years — Hugo and Eva left Bernkastel-Kues — and Germany — for Luxembourg, They went to Ettelbruck, where, an Anmeldung-Erklärung/Declaration of Arrival, dated 24 October 1938, tells us, they lived at Nordstraße. Ettelbruck was close to Luxembourg City, where Hugo’s siblings, Karl Friedmann and Klothilde Wolff, and their families lived, and also not far from Esch, where Eva’s brother Emile and the families of her two stepbrothers lived.

Once in Luxembourg, Hugo and Eva tried to bring Sitta, Ernst and Joachim to Luxembourg. Sometime in early November 1938 — before Kristallnacht — Karl Friedmann was asked if he could provide financial guarantees for the three Lewins. Karl’s reply, as noted in the Grand-Ducal Gendarmarie report of 15 November 1938, was that he could not, but that his sister, Adèle Kouperman, living in Brussels, might be able to do so. This did not happen — probably because authorities could not accept financial guarantees from non-Luxembourg sources to support the entry of German refugees into Luxembourg.

Sitta & Ernst Lewin were, therefore, in Germany in November 1938 and the Reichspogromnacht of 9/10 November. Ernst Lewin was arrested and was one of the 6,000 Jews imprisoned in Sachsenhausen; he was released over a month later, on 17 December 1938.

Imprisonment at Sachsenhausen may well have shaken Ernst Lewin’s conviction that he would move unscathed through the Nazi Regime. Henri Friedmann, Ernst’s nephew, recalls his father telling him that “Ernst was a hero of First World War, who fought for his Kaiser and received medals. So he believed that what was happening to other Jews was a tragedy but that he and his family would be protected, as the fighters of WWI had a special consideration.”

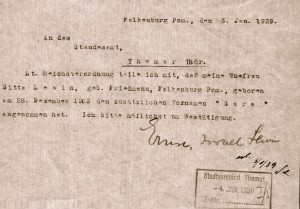

We know that the men imprisoned at Kristallnacht were released with orders to leave Germany as quickly as possible. The evidence suggests that Ernst and Sitta may have tried to enter Luxembourg, but failed: On 10 January 1939, Hugo and Eva were informed that, as German refugees, they could not legally bring other German refugees into Luxembourg.

*****

When World War II broke out, family members of Hugo and Eva Friedmann were dispersed: Johanna and Bruno were in South Africa; Sitta was in northeast Germany, Hugo and Eva were in Ettelbruck, Luxembourg; and Friedrich was in Brussels.

Sitta and her family were the first to feel the trap snap shut. “Short[ly] after the outbreak of the German/Polish war,” Henri Friedmann, Sitta’s nephew, wrote in his Yad Vashem Page of Testimony, “Sitta and her family were forced to move to Lublin.” The “Lublin Plan,” as the Nazis called this project of forced resettlement, was the first test of ‘eliminating’ Jews from Germany by moving them out of Germany to places out of mind/out of sight of non-Jewish Germans. The first region to be made judenfrei was Pomerania, where the Lewins lived.

In February 1940, 1000 German Jews, including Jews from Falkenburg, were deported from the towns of Stettin and Schneidemühle to the Lublin area. But Nazi administrators in Lublin, whose primary focus was to move the Polish Jews into ghettos, resisted the movement of large numbers of German Jews into their area. As a result, the Falkenburg Jews did not remain in Lublin but were forced to return to Germany. Yet the Nazis in Pomerania were able to achieve their goal: the Falkenberg Jews were not allowed to return to Falkenburg; instead, they were forced to go to Berlin where their presence would be tolerated until such time as deportation of German Jews became the highest priority. The Lewins lived at Grenadierstraße 4a in Spandau.

******

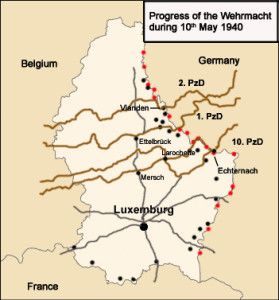

In one day — 10 May 1940 — the German army occupied the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. The assault put the Friedmanns and their immediate families in jeopardy.

In one day — 10 May 1940 — the German army occupied the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. The assault put the Friedmanns and their immediate families in jeopardy.

In Brussels, Friedrich Friedmann, “was arrested by Belgian police (with many other German refugees) as the Belgian authorities made no difference between anti-Nazis and other refugees who could really be the Reich’s agents. Due to the fast advance of the Wehrmacht, the detainees were sent to France. So my dad stayed 2 years in 2 French camps, Saint-Cyprien, and then Gurs guarded by French gendarmes.”

Hugo’s sister, Adèle, and her family fled to southern France. Adèle moved to Cahors to join her daughter and son-in-law, Olga and Paul Bernheim. Richard Kouperman initially took refuge in Mountauban.

Luxemburg was attached to Germany as part of the Trier-Koblenz region. Initially, the German administration allowed — even encouraged — emigration. After August 8, 1940, more than 2,500 Jews left Luxembourg, mostly for the unoccupied zone of France. Klothilde Wolff’s children, Johanna Deutsch, a widow, and Léon Wolff and his wife, Sophie, moved to Béziers. Karl Friedmann’s son, Richard, his wife and one daughter — aided by the Luxembourg Gauleiter — travelled by bus to Lisbon and from there to Cuba. Karl, however, did not join his son’s family and remained in Luxembourg. Having fought for Germany in WWI, Karl probably thought that “he personally was not risking very much,” as he believed that his status as a World War I veteran would protect him from Nazi aggression.

*****

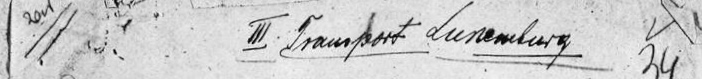

The Holocaust dealt cruelly with the families of Hugo and Eva Friedmann. On 15 October 1941, the German forbade further emigration from Luxembourg. On 16 October, the first deportation of Jews from Germany to the ‘east’ occurred — Hugo and Eva Friedmann, Karl Friedmann, and Eva’s brothers and their families were all on this transport. None survived: we believe that all were dead by the end of 1942.

On 03 Oct 1942, Sitta, Ernst and Joachim Lewin were deported from Berlin to the Theresienstadt Ghetto.

Sitta was the first to ‘die’; typhus killed her on 22 February 1943 as the death certificate, and quite detailed medical report, in the database at the Theresienstadt Archive tells us. Ernst and his son, Joachim, remained in Theresienstadt for another year and a half. Two years after their deportation from Berlin, they were transported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. Given Joachim’s young age, the two were probably murdered immediately upon their arrival on 9 October 1944.

Of those who were in France, we know the following: “My father,” Henri Friedmann tells us:

finally escaped in 1942 (a few weeks before Petain’s government started handing detainees to German authorities) and went back to Brussels, where people helped him. A funny thing is that in 1940, he was arrested, probably by Brussels municipal police, and in 1942 it was a municipal officer of Brussels City who delivered him a fake but official identity card with inscription in the population registry (this inscription makes the falseness character of the ID impossible to detect). I imagine my dad was helped by former colleagues of the Kouperman’s factory who still were in the place (the new director was a German military officer) and believed it was his duty to help Mrs Kouperman’s nephew.

In 1945, the Belgian authorities (those who arrested my dad in 1940) considered the Reich’s decision to deprive him of his German citizenship as illegal, based on racial motivation; thus they considered my dad as still being a German but, by that time, Belgian laws identified 2 categories of German citizenship: enemy and non-enemy. So my dad received a new ID with his real name (no more Frédéric François but Friedrich Friedmann) with citizenship “Allemand non ennemi”).

The family of Adèle Kouperman lived in several small villages, protected for a long time by French resistance fighters. As the roundups in southern zone increased, “someone advised the family to retreat to Saint-Géry and to contact the Décremps family, who were informed of their pending arrival.” Louis Jules Décremps, a mechanic and also mayor of the town, lived with his wife Eugénie in Saint-Géry (Lot) with two of their three children. The Yad Vashem account continues:

Louis immediately provided Richard with false identity papers in the name of Delporte. He did the same for his relatives, thus helping them to feel safer. Richard, being in his late teens and considered to be most in danger, went into hiding. The Décremps couple sent him to the Dols family, who were farmers of their acquaintances living in Bouziès-Bas. They hired Richard to work for them. Eugénie Décremps took responsibility for regularly sending a portion of Richard’s salary to his relatives remaining in Cahors to cover their living expenses. Through her intercession and endless trips, the families stayed in constant contact. The Décremps also helped the Resistance and were informed of police operations. When they reckoned that hiding Richard with the Dols family put the latter at risk, they had him “disappear” to other safe locations.

On May 5, 1944, misfortune struck the Koupermans living in Cahors and four of them were arrested. Richard wanted to go there to be exchanged for his family. The Décremps managed to dissuade him, convincing him that no one, in any case, would be released and that their own safety would be jeopardized. Richard remained hidden with the Dols family until the Liberation. On June 2, 2003, Yad Vashem recognized Louis Jules and Eugénie Décremps as Righteous Among the Nations.

At the end of World War II, three of Hugo and Eva Friedmann’s children were alive: Johanna and her family, and Bruno and his wife, Vera, who had married in 1944, were in South Africa. Friedrich and his wife, Chana, were in Brussels. While none of Eva’s siblings survived, there were survivors among Hugo’s siblings and their families: Olga Bernheim survived Auschwitz and returned to Brussels; so too did her brother, Richard Kouperman, who married Ruth Sternberg and formed a family of two daughters. Richard Friedmann and his family — a second daughter was born in 1941 — returned to Luxembourg and Klothilde Wolf, her husband, son and daughter-in-law remained in Luxembourg for the rest of their lives.

*****

In 2008, Stolpersteine were laid for the family of Hugo and Eva Friedmann in Bernkastel-Kues, and family members from Brussels and South Africa attended. [A short television report in German about the event is available here).

We hope that the years Hugo and Eva lived in Themar included much joy as they formed their family, We also hope that this page serves in some measure to honour the family of Hugo and Eva Friedmann and the contribution they made to the Jewish community of Themar.

*****

The Descendants List below identifies the members of Hugo and Eva Friedmann’s family born in Germany and the first and second generation of descendants.

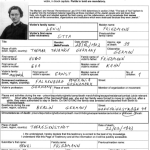

- Hugo FRIEDMANN, b. 01 Mar 1876 Neu-Ulm, murdered 13 June 1942 Litzmannstadt (Lodz) Ghetto

- ∞ Eva KAHN, b. 19 Jun 1877 Medernach/Luxemburg, murdered 04 May 1942 Litzmannstadt (Lodz) Ghetto

- 1. Johanna Sara FRIEDMANN, b. 21 Dec 1902 Themar, d. 11 May 1970 Johannesburg/SA

- ∞ Karl LANG, b. 17 Dec 1899 Frankfurt, d. 1963 Köln/Cologne (while visiting)

- 2. Wilma LANG, b. 20 Feb 192? Frankfurt, d. 15 Aug 1994 Johannesburg/SA

- ∞ Kurt KAHN/CAYE, b. 10 Jun 1911

- 2. Werner Heinz LANG, b. 27 Jan 1927 Frankfurt, d. 17 Jan 2007 Johannesburg/SA

- ∞ Leah Helman

- 1. Sitta FRIEDMANN, b. 28 Dec 1903 Themar, m. 27 Dec 1934, murdered 22 Feb 1943 Theresienstadt

- ∞ Ernst LEWIN, b. 05 Jul 1895 Falkenburg, murdered [1944] AuschwitzUBelgium

- 2. Joachim LEWIN, b. 11 Oct 1935 Falkenburg, murdered [1944] Auschwitz

- 1. Friedrich FRIEDMANN, b. 17 Oct 1905 Themar, d. 27 Aug 1967 Brussels

- ∞ Chana MAUR, b. 14 Nov 1912 Daleszyce/Poland, m. 30 Nov 1938, d. 29 Jan 1992 Belgium

- 2. Henri FRIEDMANN, b. 1947 Uccle/Belgium

- 1. Bruno FRIEDMANN, b. 15 Oct 1908 Themar, d. 18 Jul 1980 South Africa

- ∞ Vera MARCUS, b. 01 Sep 1912 Pirmasens, m. 02 Jan 1944, d. 07 May 1989 South Africa

- 2, R. FRIEDMANN, b. 1947 Johannesburg/SA

- 2. S. FRIEDMANN, b. 1951 Johannesburg/SA

*****

Notes:

1. The Friedmanns did not come from Thüringen and were not, as far as we presently know, related either to the other Kahn family in Themar or to the Friedmann family of Berkach.

2. The spelling of Bernkastel-Cues changed over time: from two ‘c’s — Berncastel-Cues —at the beginning of the 20th century; then to Bernkastel-Cues from 1927; and then two ‘k’s from July 1936 on, Bernkastel-Kues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the families of Hugo and Eva Friedmann’s children — Johanna, Friedrich, and Bruno — for their contributions to our knowledge. Henri Friedmann’s submission of Pages of Testimony in 2008 to honour his aunt and uncle and cousin — Sitta and Ernst Lewin and their son Joachim — provided critical clues that guided the research and growing knowledge of the family.

We also wish to thank two researchers for their contributions: first, Dr. Marianne Bühler provided new information to our knowledge of the family in Bernkastel-Kues and dates of marriage, departure, etc. Her work on the Jewish community of Bernkastel-Wittlich can be found here.

The new information from Dr. Bühler led in turn to contact with Linda Licina-Gedink who leads a project for the Medernach Municipal government is, as she wrote in April 2014, “to try and compile all persons that were born, married or died in Medernach, and this by entering the details from civil acts one-by-one. I have finished now all the acts that are available from Medernach on www.familysearch.org (till 1923) and I am now trying to complete the picture by finding out, where those people who did not stay in Medernach have landed.” Her project results can be found at: http://medernach.myheritage.com.

If you have any information or questions about the Hugo & Eva Friedmann family, which you would like to share, please contact Sharon Meen @ [email protected] or [email protected]. We would be pleased to hear from you.

Sources:

Alemannia-judaica, Bernkastel(Stadt Bernkastel-Kues, Kreis Bernkastel-Wittlich) Jüdische Geschichte/Synagoge

Alemannia-judaica,Jüdische Geschichte Illingen (Kreis Neunkirchen, Saarland

City of Themar, Archives.

German Archives, Memorial Book

“Gurs,” and “St. Cyrpien.” Learning about the Holocaust through Art.

JewishGen, Database for Family of Raphael and Nanette Kahn of Schweich Germany.

JewishGen. Lodz Ghetto Hospital Records

Themars jüdische Geburtregister 1876-1937, Staatsarchiv Meiningen.

Themarer Zeitung, 1904-1909.

Yad Vashem, Pages of Testimony, submitted for H. Friedmann, E. Friedmann, S. Lewin, E. Lewin, J. Lewin, 2008.

Willi Körtels: Die jüdische Schule in der Region Trier. Hrsg. Förderverein Synagoge Könen e.V. 2011. pp. 150-151. Online zugänglich (pdf-Datei).

The laying of Stolpersteine and the research and press reports accompanying these events are providing historians with welcome information — and sometimes more questions than answers — in their search for traces for communities such as that of Themar. See, for example, “Ein Stein, ein Mensch,” volksfreund.de, 29 Oct 2008, and D.B. Broadman, “A return to Germany, a dedication for Kristallnacht,” The New Jersey Jewish Standard, 06 Nov 2009.