by Robert L. Strauss

A grandmother’s story, never told before, opens a path of understanding and forgiveness….

We left Weißenbronn on the same road that my great-grandfather once used to transport his cattle. This part of Bavaria is not spectacular, it is simply a hilly landscape.

As we drove north, reflecting on the simple decency of Mrs. Hoffmann’s actions, we realized that our feelings about Germany were changing. We had not encountered any skinheads, had not heard any anti-Semitic remarks. It was very difficult to reconcile our experiences in Weißenbronn with our feelings and knowledge about the past.

Themar, where my father Henry Levinstein was born in 1919, is probably little more than 150 km from Weißenbronn as the crow flies. Although it was liberated by the U.S. at the end of World War II, it was assigned to the Soviet zone. Somehow I expected, even hoped, that Themar would be a tiny village, standing still in the 20s and 30s of this century, so that I could see where and how my father had grown up.

We spent the night between Weißenbronn and Themar in Meiningen, a town whose name my father had mentioned, I remembered. A few blocks from our hotel, Nina spotted a Star of David on a small memorial plaque. The simple German inscription on this plaque enlightened us that the Meiningen synagogue had stood on this spot, burned to the ground in November 1938 during the Reich-wide pogroms. Across the street, on the other side of a meadow, a large ginger-colored hotel was under renovation. The synagogue had had a respectable location.

Directly in front of Themar and the remains of its fortification walls, welcome signs proclaimed: ,,Themar – 1200 years: 796-1996″. Themar was celebrating its 1200th anniversary.

“What are you going to do now?” asked Nina when we arrived. My plan was unchanged. We would go to the cemetery and see what could be found there. Unlike Weissenbronn, I thought, there might still be people living here who had known Dad or his parents. We just had to find them.

As we drove into Themar, a UPS truck overtook us. A billboard pointed out that the nearest McDonald’s was only 6.5 km away. Clearly, Themar was no longer the Themar of Dad’s youth.

We had arrived around lunchtime. Nina was hungry, so we stopped at a bakery. We waited until there was only one woman behind us before we finally bought something. We pointed to a few things we wanted and used our fingers to agree on the price. “Are you going to ask now?” remarked Nina . – I felt uncomfortable asking about the cemetery. We were, after all, in the former East Germany. We knew that bad things had indeed happened in Themar. I did not know how we would be received. – Hesitantly, I began my ten-second inquiry about the Jewish Cemetery. We were told that it was in the neighboring town of Marisfeld. The woman behind us, who spoke no English, seemed quite interested and followed us outside.

At that moment, her English-speaking daughter appeared. We explained to her that we wanted to find someone who could talk to us about Themar before the war. She translated this and her mother replied quite enthusiastically with many nods of her head, “My mother.”

“I’ll show her the picture,” I said to Nina. By that I meant the photo of Dad and his mother from the early 1920s. “Why?” she asked, continuing to be skeptical. “You won’t be able to recognize anything.” I showed the two women the sepia-brown child’s picture of Dad. To our complete surprise, they immediately began nodding. They knew the place. It still existed. In a town with 1200 years of history, buildings tend to stay in place.

The older woman got into our car. A few blocks down, she asked us to pull over and pointed out the detail that had made it easy for her to identify the place. The top floor of the building had three small arched windows that were clearly visible in the photo. Our fellow passenger, Ingrid Saam, lived just around the corner.

We thanked her, said goodbye, and set out to find the exact spot from which the picture had been taken. We could see through hedges into backyards, but could not find a way inside. As we walked back to our car, a teenager wearing a “No Nazis” t-shirt approached us. I still felt uncomfortable asking strangers about things concerning Jews, but I figured he would be understanding. “No,” he told us in English, he didn’t know anyone who knew anything about the history of the neighborhood. He suggested we talk to the English teacher at the school around the corner.

As he was leaving, Ms. Saam reappeared. We explained to her that we intended to get the school’s English teacher to help us. But first we wanted to find the spot from which the picture had been taken. As we walked back our way, Mrs. Saam pointed out the many houses that had once been Jewish. She didn’t know the Levinstein family, but knew which house had housed the synagogue and school, and believed that this might be the place we were looking for. It was located, around the corner, on Ernst-Thälmann-Str., named after the Communist leader who had died in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Previously, this street was known as Oberstadtstraße.

The house was freshly painted a bright sky blue. Geraniums sprouted from flower boxes on its windowsills. There was no longer any connection to the Jewish community or the Levinstein family. “Hair & Beauty” occupied the second floor. The expansive storefronts were filled with photos of beautiful women, styled with the latest hair care products. In the backyard, apples ripened on several small trees. Behind the garden with fruit trees was a small area of lawn and from there you could see the building in the photo. I held the cracked, yellowed snapshot up at arm’s length.From where Nina and I now stood, the perspective was exactly like the one where my father and his mother had stood 70 years ago. We had finally found the right place.

We went back to the school hoping to find the English teacher. “Can you understand that?” said Nina. I, for one, couldn’t. In a town where no Jew had lived for 54 years, the school had been named after Anne Frank. Mrs. Saam hurried into the school and returned a few minutes later with Mrs. Kammbach, the English teacher. “My lunch,” she said, pointing to the peach in her hand. It turned out she was a friend of Mrs. Saam’s family.

Mrs. Saam led us around the block. There was a collapsible wheelchair in the entryway of her home. The winding stairwell was made even narrower by the twisting metal rails of a Handycap lift system. On the third floor, she introduced us to her 73-year-old mother, Waltraut Wilhelm. Mrs. Wilhelm came out of the kitchen on crutches, turned and dropped into a chair. Like her daughter Ingrid, she looked almost picture-perfect: rosy cheeks, snow-white hair, a broad, beautiful smile and intensely bright blue eyes. I began my conversation, “My father, my grandfather, my grandmother from Themar. Names Levinstein.”

Mrs. Wilhelm nodded and began to tell and Mrs. Kammbach translated. Mrs. Wilhelm remembered the Levinstein family well, she told us. She had passed the house at Oberstadtstraße 17 every day on her way to school. She had never been inside, but she believed that the Levinsteins lived on the second floor, (where “Hair & Beauty” was now), that the Jewish school was on the second floor, and that the third floor was a community center.

She described Dad’s father Moritz in detail. She remembered him as a man with thick glasses and a round face – just as he looked in photographs. She remembered Nanette, Dad’s mother,in more detail. She was “a beautiful lady, a fine lady,” she said.

Soon the strudel that Mrs. Saam had bought at the bakery was dished up, along with some pastries. Coffee and tea were served, and we sat around the table decorated with lace tablecloths. The apartment was not spacious, but filled with plush armchairs, all sorts of small objects, pictures of the Alps, of flowers and animals. Until we had been invited to a few German apartments, I had not realized how strange and German my grandmother Nanette’s home in America had been.

We explained to Mrs. Wilhelm that the reason for our visit to Themar was to see this small town about which I had heard so little. I explained that the family’s history in Germany, as we understood it, had not been very happy, and it followed that it was very rarely talked about. I told her and another daughter, Mrs. Goldschmidt, who had come along, that Dad had died ten years ago and his mother five years later. So there was really no one left who knew much of the story. Would she be willing to tell us what she knew?

Mrs. Wilhelm began to tell us what she remembered. She had been young then, just a teenager. At that time, she said, there was already a certain amount of enthusiasm in Themar for the Nazis. The living situation had been bad and it seemed to be getting better now. Like many of her friends, she was carried away by a surge of enthusiasm for something new. She paused often and shook her head, as if wondering how she, a young girl of that time, could be the woman of today.

She knew that Moritz had been arrested in November 1938 during the so-called “Kristallnacht” in Meiningen. She remembered that she and her family were surprised because he was popular in the community. She had not gotten very far with her story when she began to cry. Her eyes, which were so intensely blue, shimmered. After she started crying, we all started crying. She said that not long after she heard that Moritz had been arrested, the news reached town that he had committed suicide. That he had jumped off the train and into the river on the way back to Themar.

When Mrs. Wilhelm saw that Nina and I were crying, she explained that she would not have told us this story if she had known that it would upset us so much. But she thought it would be good for us to know what she knew, and that was why she had agreed. She said that except for a neighbor who now lived in Florida, she had never talked to anyone about what had happened – not even her daughters, who sat and cried with us.

We explained to her that what she had said was more or less the story I had heard at home, which could never be confirmed by anyone. We mentioned that it would have been very unusual for a religious Jew like Moritz to take his own life, making it difficult for people at home to believe this story. Some believed that he might have been beaten and thrown into the river from the train.

She thought about this for a long time. She told that the Levinsteins’ home, the school and the synagogue had been very badly devastated. That the story was going around Themar that Mr. Levinstein, hearing about the destruction of his temple on his way home, was so upset about it that he took his own life. She had not known that he had been taken to Buchenwald for several weeks and only then released. She paused and thought again. She said that there had never been any people who had come forward as witnesses to the train ride. After a long time, during which she paused and wiped away more tears, she said, yes, it could have been as you say.

We knew that one of the intentions of “Kristallnacht” had been to frighten Jews into leaving Germany. But Mrs. Wilhelm said that Moritz` death in Themar was not used for this purpose. He was a popular man. She felt that it would not have been to the Nazis` advantage to brag about killing him. Perhaps the story of his jumping to his death had been spread to keep the local people quiet.

We talked about other things. I asked her if she had ever heard of a “Dixie,” a car my dad had told me had belonged to his father, as I recalled. It was so small, my dad told me, that it sometimes flipped over when it went around a curve.

Yes, yes, yes, she said laughing, her father had had one like that too. It was a two-seater, and a third person could sit in the trunk, she said. Sometimes it would tip over on a turn, but it was light enough that you could just get it back up and keep going.

We had moved on to happier topics and Mrs. Wilhelm began to gesticulate as if she were playing “bake-bake-cake.” “Matzo,” we heard her say. The teacher explained that Mrs. Wilhelm remembered that Dad’s father made special cakes, especially around Easter time. After I translated the word, Mrs. Kammbach asked, “What is matzo?”

I thought it was a bit strange to retell stories from the Bible in a Christian country. We told how the escape from Egypt had occurred and why Jews eat matzo (leavened bread) during Passover and that the Last Supper (“Last Supper”) had indeed been a Seder meal. I remembered that a cousin had once told me that Dad’s father had been nervous about making the matzah. He hadn’t declared it as income and the Nazis had put pressure on him to pay back.

“What happened to the other Jews who had stayed in Themar?” asked Nina. Before Hitler, there had been about 35 Jewish families in Themar. Not all of them had been captured or expelled. Immediately, Mrs. Wilhelm’s face reflected her changed mood. Her face darkened.

She told us that in 1942 all Jews were ordered to report to the train station at 8 am. She remembered this clearly. Mrs. Kammbach continued to translate, but shortly after she began her story, Mrs. Wilhelm began to cry and wipe her face with her hands, unable to talk further. Her daughters to her left and right tried to comfort her, but even after so many years it was hard for them to bear the image conjured up from the past.

“What did she say?” asked Nina. “She said that they were driving the Jews to the train station, and that was very unpleasant,” Mrs. Kammbach told us. “There was a Jewish woman there who had broken both her legs, and the Nazis took her… This is where she stopped talking.”

Someone of us must have asked how it was that Mrs. Wilhelm could see all that, and Mrs. Kammbach explained. Mrs. Wilhelm had polio. Her window faced the street where people were herded along like a herd of cattle. Paralyzed, unable to use her own legs, unable to leave the scene, she watched as the Nazis beat the Jewish woman with the broken legs, who also could not move independently.

Mrs. Wilhelm continued to sob. The beatings she had witnessed so many years ago were burned into her memory.

We spent three hours at Mrs. Wilhelm’s table. While we were talking, her younger daughter had called the mayor in Marisfeld to arrange a visit to the cemetery.

We asked them if they had seen the movie “Schindler’s List.” One of the daughters had seen it, but Mrs. Wilhelm herself had not. She did not think she could stand the whole movie. Her daughter had told her the content, and that was enough for her, she said.

Before we left, we talked about the changes they had experienced since reunification. They, too, had never thought anything like this would happen. They, too, had felt tremendous joy when their country was put back together. Mrs. Wilhelm said that when she saw the Alps for the first time five years ago, it was one of the most moving experiences in her life.

The mayor of Marisfeld had promised to meet us the following morning. That afternoon the sunlight was so lovely that I suggested to Nina that we drive to Marisfeld anyway, if only to take pictures.

The three-mile drive was on a small, two-lane road that made a 90-degree turn after every half mile as it traversed woods and farmland. A handmade signpost stood at the last right-angle turn just before Marisfeld. A wooden arrow pointed up an overgrown dirt road to the Jewish Cemetery.

Like the cemetery in Rödelsee, the one in Marisfeld occupied a beautiful spot above the town. Cattle grazed in an extensive pasture beside the road.

It was the “golden hour” when the setting sun bathed everything in a deeper red light. Someone had set up a wooden table and bench right next to the wooden picket fence and quaking poplars surrounded the small cemetery.

The cemetery was much smaller and better kept than the one in Rödelsee. The grass was short and soft. One could not find a lovelier, more peaceful place than the bench overlooking the place.

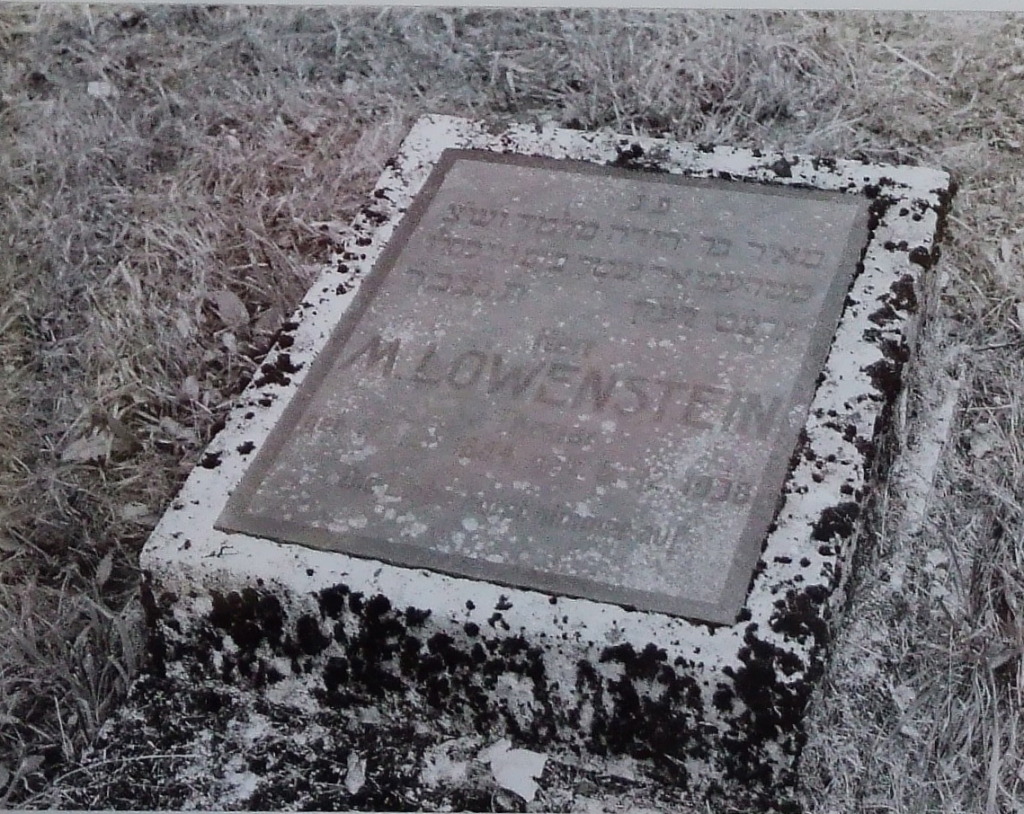

The 50 or so graves were laid out in order, from oldest to last. They went back several hundred years and came to an abrupt end, a little to the left of center in the first row. Without going inside, we could make out the name on the last grave, which was closest to the gate. “M. Löwenstein” was written on it. This was the grave of Moritz. Sometime on the way to America the name had become Levinstein. “Born November 17, 1884, died December 6, 1938.” [Notes: Henry Levinstein did NOT change his name; it was a mistake by the Steinschnitzer cemetery]. Less than a month after Kristallnacht. “Love never ceases,” was inscribed on the headstone. I was told that this was an old-fashioned German phrase, but its meaning is eternal. “Love lasts forever,” or “Love never dies,” my grandmother had written. “It’s like the beginning of the end,” Nina said, referring to the shortened row of graves that ended with Moritz.

We took pictures and made a few notes, wondering why the Jews had been given such a nice place for their cemetery. Possibly we could have found other people who would have known more. We could have asked to see the local archives. But Mrs. Wilhelm’s narrative was enough for us. We had felt the pain of that memory. We did not feel the need to probe deeper.

We had come to Germany without a plan, without guidebooks or dictionaries, and to our surprise we had found out much more than we had imagined. Our underlying anger at and fear of the Germans had subsided. We had uncovered some of the traces of our long lost relatives.

But I had intended one more stop. After his arrest, Dad’s father had been taken to Buchenwald. Surprisingly, we didn’t know where it was. To our surprise, some Germans we asked didn’t know either. Their astonishment raised for me the question of what is remembered and what is forgotten or never learned.

Buchenwald is a suburb of Weimar, which, like Themar, is also in East Germany. The drive there was the most delightful of all. At one point we found ourselves on a one-lane path, a dirt forest road, for 15 miles. We had no idea where we were. There were no signposts and only a few abandoned homesteads in the dense forest. As we bumped through deep wheel ruts and over sharp rocks, Nina repeated several times that she didn’t think this was the right road for a woman 5 months pregnant.

Nina had not wanted to go to Buchenwald. “I’m not sure I can take it,” she said. But I wanted to go there. It seemed the appropriate way to complete our journey.

The road to Buchenwald itself led through a vast lonely forest. Paths that had been left to themselves many years ago disappeared into the undergrowth and one wondered where they once led. A huge Soviet-style monument, adorned only with the date “1945,” is the first thing you see.

“What is that?” asked Nina as we passed a structure near the visitor center. It was the railroad siding. It took no imagination to conjure up the image of trains stopping here and unloading their cargo.

We arrived just as the hourly film screening began. At ten o’clock in the morning, the wide auditorium was almost empty. The film was in German, but even without narration it would have been easy to understand. There were scenes of Eisenhower, Bradly and Patton visiting the camp, film clips of American soldiers turning their heads away from the stench, their lifeless bodies stacked like bundled wood.

Two Germans in their early 20s sat behind us, their legs on the back of seats in our row. They were both grunge rocker types, ragged clothes, fluorescent hair, pierced and tattooed bodies. The movie hadn’t been running long when one of them fell asleep. For the first time since we had come to Germany, I felt anger rising inside me. For a few minutes I tried to ignore his snoring. I couldn’t.

“Hey!”, I shouted. “This is no place to sleep. Wake up!” He shook himself awake, possibly not having understood anything I had said except my tone. They stayed for the rest of the movie and then left. Our eyes did not meet.

Buchenwald was not one of the main extermination camps. It was a transit station, an industrial zone for slave labor and its administrators. By the end of the war, 51,000 people had been killed there, many of whom, perhaps the majority, were not Jews. By the end of 1938, 10,000 Jewish men who had been arrested on Kristallnacht had been taken to Buchenwald, including Dad’s father. Most of them were released shortly thereafter. The systematic extermination was not to begin for another few years. It was on the way home when Moritz’s life ended.

As we left the film presentation, buses and cars began to fill the spacious parking lot. I wasn’t sure if any of us really wanted to take the tour of the camp at all. How could we reconcile this place, high on a hill, surrounded by dense, silent forests, above a city famous as one of the great centers of German intellectual life, with the past? How could we relate the wonderful experiences we had had to what had taken place here? Why were we here at all, I asked myself. We had not traveled to Germany to continue to hate it, but to try to understand it. So what was the real reason for coming to Buchenwald? We had seen the movies, read the books, been to the museum in Washington. Our souls needed no further cleansing.

We saw the two German punks get into their car and drive away. They did not go through the gates of the camp, over which the words “To each his own” (“Each to his own”) are hammered in steel. They paid no attention to the hands of the tower clock, which were forever stopped at 3:15 in the afternoon, the moment the Americans liberated the camp. They did not look over the 40 or so gravel-covered rectangles marking the spots where the prison buildings then stood. Where Gypsies, criminals, Jews, homosexuals and other flotsam of life, what was to be exploited and “purified” were housed. They did not pass through either of the two buildings that remained on the site.

One was a museum, which presented an excellent chronology of the Third Reich – one that explained how it could happen, how all the various “players” who could have prevented it allowed it to happen. Perhaps the two would have learned nothing from the museum, or they would have preferred not to believe what was documented there in such detail.

But it was the other, smaller building, what was to the right of the parade ground, where they really should have gone. One learned about the history of Buchenwald through the atmosphere of this building, not through the few notices on the walls. At the entrance, a small plaque in the national languages of the major post-war powers indicated that this building, in the absence of graves, was to be regarded as the final resting place for the thousands who had passed through the door through which we were about to enter. Visitors were asked to view this as a memorial site. It was the crematorium.

The first rooms were unremarkable and the path led back outside. The doors were massive and closed with a heavy, brisk motion. There were no directional indicators. There was only one path to follow.

Nina stayed outside while I went to the basement. It was a hot summer day, but as I walked down the few steps, the piercing cold of the thick concrete drove away the heat. There were hooks embedded in the walls. At the end of the room stood a wide freight elevator, ready for its load. I called Nina to come down. We were alone. Neither of us could shake the cold. It was the kind of cold that creeps up through the soles of your feet and penetrates your bones. Perhaps this had become meaningless to those who had passed through. I wondered if it could have been any colder in the winter.

There were no descriptions or plaques at the top. There were no historical photos. The four ovens with their metal doors open, ready to be loaded, as well as the elevator ready to be unloaded, needed no explanation. There were a few wilted bouquets of flowers between the ovens. There were chains of tiny origami paper cranes. Nina and I had seen tens of thousands of them draped around the Hiroshima memorial in Japan. Here there were much fewer. Today Hiroshima is a huge industrial city. Buchenwald has remained a small town, in many ways still hidden in the forests.

We stood alone in the room. We said nothing. It was a solid, well-built building and no matter what noise there was outside, it didn’t reach here. Nina began to sob, deep, choked sobs, tears streaming down the inside of her throat.

Outside we passed the Memorial to the Jewish Victims of Buchenwald, which was inscribed in German, English and Hebrew. “For the children yet to be born,” it said.

We left Germany that same afternoon. We had gone there, perhaps expecting to find confirmation for all our years of simmering anger. What we found was far from what we imagined. The people we met—thoughtful, concerned, compassionate—made us think about our own biases. The unfocused bitterness we had instinctively felt toward Germans and everything that was German had been banished. We no longer thought of Germany as the personification of all evil for today and all times, but we wondered how long anger over the past would remain in the heart. We still don’t know the answer to this day. All we know is that for us the time is shorter than we thought.