Please note: This page is under construction.

Thank you for your patience

See as well:

The Home Purchase Contracts & Theresienstadt Ghetto

Deportation of members of Themar’s Jewish families to Theresienstadt Ghetto

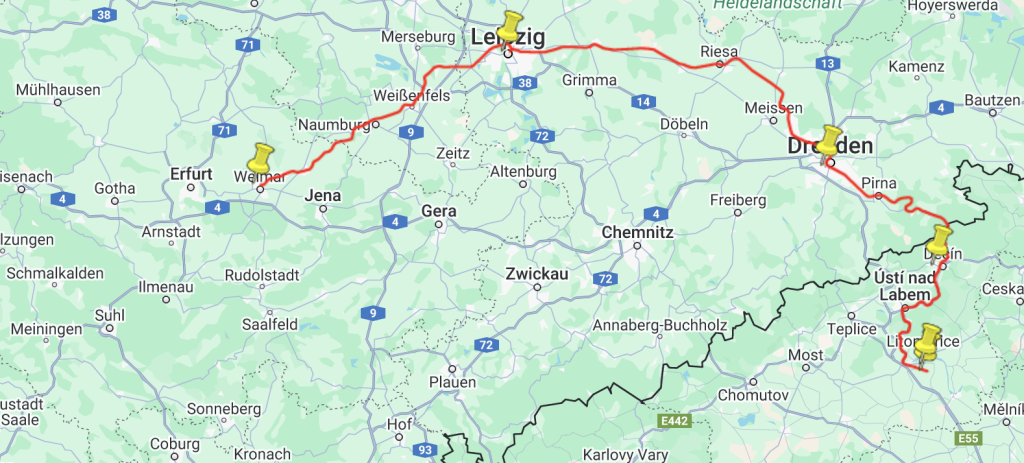

Transport XVI/1, Train Da 517 from Weimar, Thuringia, Germany to Theresienstadt Ghetto, Czechoslovakia on 19/09/1942

This train began its journey in Weimar (Thuringia) on September 19, 1942. In Weimar, the elderly Jews, who had been forced to live in “Judenhäusern” (houses designated for Jews), were taken to the train at the freight train station in Ettersburger Straße from the assembly site at Marstall. Among them were 60 elderly Jews who had been brought from Eisenach, as well as 13 Jews from Gera, one Jewish woman from Weida and an uncertain number of Jews from Nordhausen in Thuringia. Fifteen elderly people from Mühlhausen in Thuringia were also part of this transport. On September 19, 1942 they were brought from the assembly site at Bastmarkt on foot to the freight train station, from where they were presumably brought to Weimar. The oldest member of this group was 84 years old, the youngest 56.

In Leipzig 440 Jews joined the train. Of these a minimum of 336 were from Leipzig. There were also 68 members of the Jewish old age home in nearby Halle (Saxony) who had been brought directly to the train station by bus, smaller groups of Jews from Gera, Jena, Altenburg and Nordhausen, as well as single persons from various towns in the vicintiy such as Bleicherode, Erfurt, Meiningen and Sangershausen. It is not known how and when exactly the Jews from these surrounding towns were brought to Leipzig, though it can be assumed that they arrived in Leipzig no more than two days before the transport left Leipzig, as the assembly camps in Leipzig were made available to hold Jews for only two days.

On September 19, 1942, Transport XVI/1 departed from Leipzig and arrived in Theresienstadt the following day. The train was designated “DA 517.” It was the first of 19 transports from Leipzig to Theresienstadt during the war, which were made up mainly of elderly Jewish deportees (Alterstransporte), and also the largest. There were between 877 and 880 people on this transport.

The train’s route took the deportees from Leipzig and then to Dresden along the river Elbe to Decin (Tetschen), Usti nad Labem (Aussig) and finally to Bohusovice (Bauschowitz). The deportees were taken off the train at Bohusovice station and forced by the awaiting SS personnel and Czech gendarmerie to walk the approximate 3 km to Theresienstadt, carrying their backpacks.

Fritzi Moldovan from Leipzig was on that transport. In her postwar testimony she testifies that upon their arrival in Bohusovice they saw Jews from Theresienstadt with bands on their arms working at the train station. According to her statement, the walk from Bohusovice to Theresienstadt took between one and half to two hours, as people had many things to carry and wore as many clothes as they could since they had no idea when or if they would return to their homes. Only people who were unable to walk were taken in trucks.

The transport was given the reference XVI/1 in the Theresienstadt ghetto listings where the Roman numeral XVI refers to Leipzig. In Theresienstadt many of the elderly Jewish deportees who had arrived on these transports died of hunger and disease during the following months.

Others were later transferred to extermination camps in the East where they were murdered. According to historian Alfred Gottwald, at least three persons from this transport were transported from Theresienstadt to Treblinka in October 1942, 52 were transported to Auschwitz in early 1943, with 105 following during 1944. Ninety two persons of the 877 deported on this transport survived.

Of the 1,216 Jews who arrived in Theresienstadt from Leipzig, around half actually came from that city; the others boarded the same trains which stopped in Leipzig en route to Theresienstadt, or they were taken to the assembly camp in Leipzig from the surrounding areas.

The Heimeinkaufsverträge/Home Purchase Contracts

As early as the beginning of September 1942, Jews had to conclude a so-called “home purchase contract” with the “Reich Association of Jews in Germany” for the Theresienstadt camp. By this time, the Reich Association of Jews in Germany had lost its independence and, on the instructions of the Nazi authorities, concluded these contracts with the persecuted Jews earmarked for transportation to Theresienstadt. Through this perfidious procedure, the many elderly people, often living in Jewish old people’s homes, were led to believe that they had secured material security for the rest of their lives (“guarantee of accommodation, food, care and medical care for life”) in order to gain access to their assets. In these contracts, they were assured that they would receive medical and other care until the end of their lives, in return for which they handed over all their possessions to the Nazis. Ultimately, the contracts served to plunder the Jewish citizens as smoothly and comprehensively as possible. The Jewish tradition of assuming social responsibility for poorer fellow human beings was also shamelessly exploited. For example, the home purchase contract with Cäcilie Rosenbaum stated: “It is the duty of all persons designated for communal accommodation who have assets to cover not only the costs of their own accommodation with the purchase amount to be paid by them to the Reich Association, but also, as far as possible, to raise the funds to provide for those in need.”

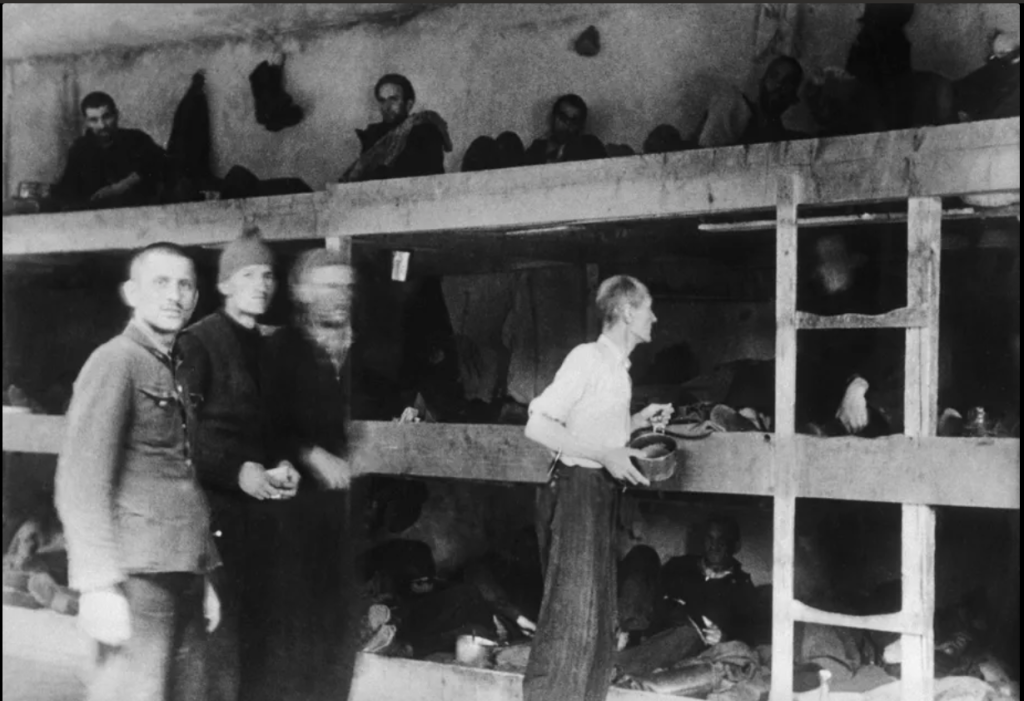

With such expectations, the Jews were traumatized by their arrival in Theresienstadt when the harsh reality of the Theresienstadt ghetto hit the deceived old people. The old people traumatized in this way did not survive hunger, disease and the other sufferings of camp life for long. Their mortality rate was therefore particularly high. In the fall of 1942, 46-50 per cent of the prisoners were over 65 years old. However, this percentage quickly fell sharply, partly because a short time later old people were no longer deported to Theresienstadt but directly to the extermination camps in the east. In this way, the SS commandant’s office was able to reduce the problem of overpopulation in the ghettos and the risk of infectious diseases. The period during which Theresienstadt could be described as a “ghetto for the elderly” lasted only six months.

Those elderly people who remained in Terezín for a longer period of time formed one of the poorest groups in the ghetto, although the Jewish self-administration made efforts to improve their situation by providing them with houses where they could receive basic care and other assistance.

For more detail, see this table linking the families of Themar and their respective Heimeinkaufsvertrag in Arolsen Archives.

For families with non-digitized contracts or Heimeinkaufsvertrag mentions, see this page.