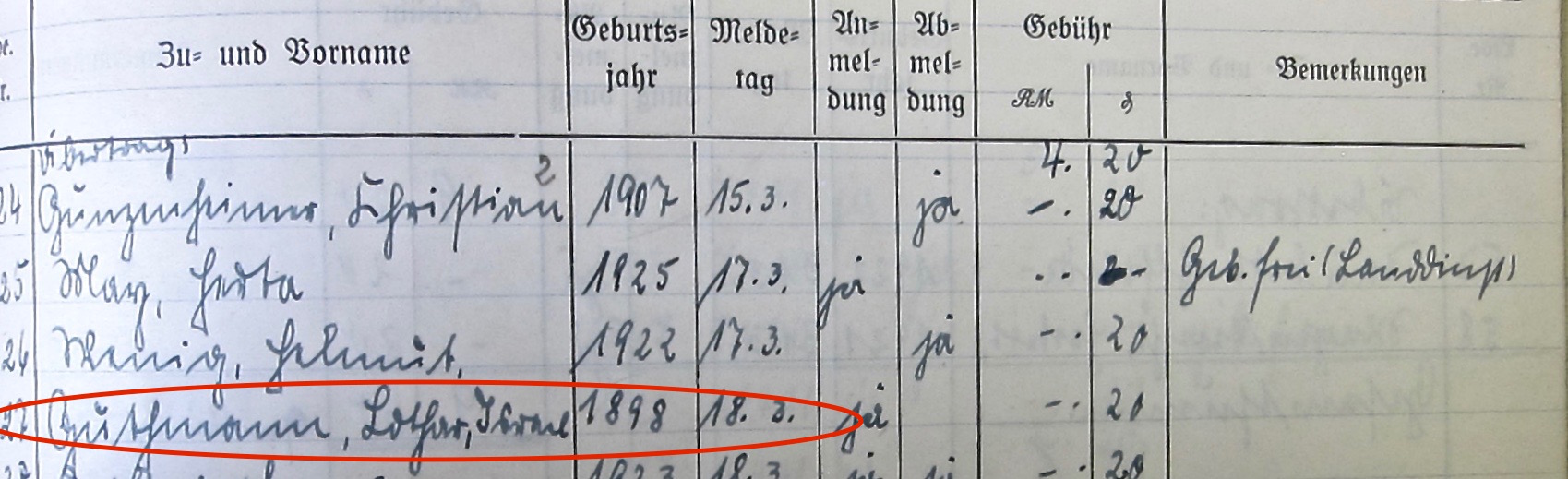

Quelle: Stadtarchiv Themar, Ordner 109

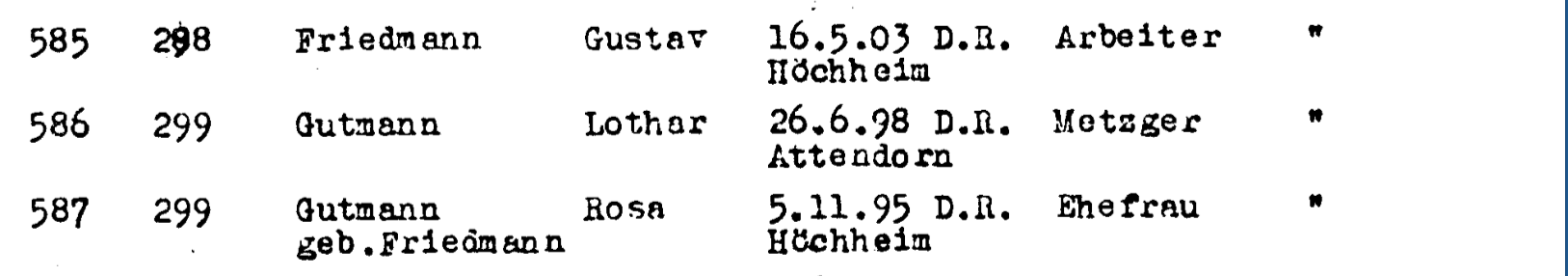

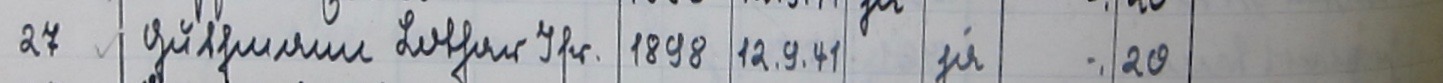

Quelle: Stadtarchiv Themar, Ordner 109

On 18 March 1941, Lothar Israel Guthmann, b. 1898, paid the fee of 20 pfg to register his arrival in Themar; six months later, on 12 September 1941, Guthmann once again paid a fee to register his departure.

The entry was startling because the name Guthmann — spelled with ‘th’ — rang no bells. “Who was Lothar Guthmann?” we asked. “And why was he in Themar in the summer of 1941?”

The first thought was that perhaps Themar’s Standesamt had misspelled ‘Guttmann,’ a name associated with Themar through the Wertheimer and Frankenberg families. Perhaps some family connection had brought Lothar to town.

But a quick search of the Deutsches Bundesarchiv Gedenkbuch identified a Lothar Guthmann who had been deported from Würzburg to Krasnystaw in occupied Poland. As well, there were newspaper articles about the Stolpersteine laid in 2008 for Lothar Guthmann and his sister Helene in the town of Attendorn, their birthplace.(1)

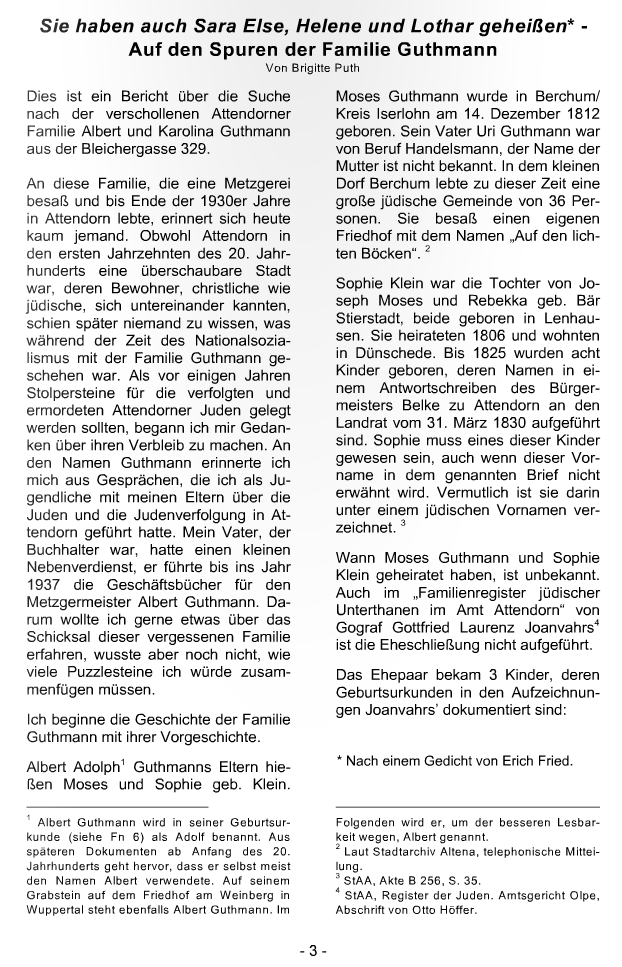

And then we found the detailed, and richly illustrated, article by Brigitte Puth, Sie haben auch Sara Else, Helene, und Lothar geheißen: Auf den Spuren der Familie Guthmann, published in 2011.(2) Ms. Puth was the daughter of Franz Henze, who had been bookkeeper to master butcher Albert Guthmann, Lothar’s father; she had been instrumental in the laying of the Stolpersteine for Lothar and Helene.

After the laying of the Stolpersteine in 2008, Puth continued her research into the Guthmann family story. Summarized — very briefly — it is as follows: in 1879, Albert Guthmann came to Attendorn from Gandersheim; by 1891, he had set himself up as a master butcher and, in the same year, he married Karolina/Lina Fränkel, b. 1866 in Biblis. Albert and Lina had four children: the first, Ernestine Sophie, died as an baby. The second, Sara Else, married Max Neugarten with whom she had two children. The Neugartens were able to escape before WWII began. Else Sara and Max Neugarten left Germany in August 1939 for Columbia to join son Kurt who had emigrated before Kristallnacht; Margot left on 5 May 1939 for England and a year later joined her family in Cali.

Albert’s and Lina’s youngest children, Helene and Lothar, were both trapped in Europe and murdered. In 1923 Helene had married Abraham Teitel, b. in Sarnow; they had settled in Herne and had three children, the last of whom was born on 11 October 1938. On 29 October 1938, Abraham and 14-year-old Wolf-Werner were rounded up as part of the ‘Polenaktion/Polish Action,’ the deportation of about 17,000 Polish Jews resident in Germany to the German-Polish border. The Nazi Regime considered Abraham’s nationality to be Polish and therefore his family as well. On 1 July 1939, Abraham was allowed to return home to organize his family for permanent departure. On 30 July 1939, Abraham, Helene, Waltraud and Isidor Teitel left Germany forever (3); the date and place of their murder is not known.

Wolf-Werner Teitel managed to escape: on 20 April 1939, supported by the Polish-Jewish Relief Fund,Werner left Poland on a Kindertransport, travelling via Gdynia first to England and then on to Australia.(4) The USHMM photo archive includes this photo of the young men: “Group portrait of German Jewish refugee youth on the deck of the SS Oronsay while en route from England to Australia.” Here he married Betty Aloni, b. 1924 in Lozma Poland, formed a family of three children, and lived until his death in 2006. In 2015, one of Wolf-Werner Teitel’s daughters visited Attendorn. (5)

*****

And so we return to the two questions that prompted this search: Who was Lothar Guthmann? Why was he in Themar in summer 1941?

With thanks to Brigitte Puth, we now know the answer to the first question: Lothar Josef Guthmann was a German Jew whose family roots stretched back into the 1700s. Born in 1898, he was the youngest of four children of Albert and Lina Guthmann. He was born in Attendorn in Nordrhein/Westfalen, a town of some 3,000 residents in 1900, of whom about 46 were Jewish. Lothar followed the same occupation as his father, and grandfather before him, namely, master butcher. On 23 December 1928, he married Rosa Friedmann of Höchheim — see B. Puth, p. 19, for a photograph of the marriage — and moved to that town. Lothar and Rosa did not have children and lived with Rosa’s mother, brother Gustav and sister Hedwig.

From the mid 1930s on, Nazi persecution hit Lothar Guthmann and his family relentlessly. On 10 November 1938, the Reichspogrom known as ‘Kristallnacht’ caught Lothar and two brothers-in-law — Gustav Friedmann and Max Neugarten — in its trap; Lothar and Gustav were sent to Buchenwald, Max to Dachau. While we know that Lothar was probably released, as were all the Kristallnacht prisoners, in order to pursue any and all chances of leaving Germany, no traces of Lothar’s efforts to emigrate have been found at this time. [As noted above, the family of Lothar’s eldest sister, Sara Else, was able to leave.]

By summer 1941, therefore, Lothar was the only member of his family still in Germany: his father, Albert, had died 12 May 1941 in Köln while Lothar was in Themar. He would have had little hope of emigrating: although it was still possible for Jews to emigrate voluntarily when he had arrived in Themar in March 1941, this was no longer so in September 1941. Hitler’s decision to force Jews to emigrate to the “East” occurred on 14 September 1941 two days after Lothar’s departure from Themar.

Lothar probably returned to Höchheim in September 1941; seven months later, on 25 April 1942, Lothar and his wife, Rosa — their names spelled without the ‘h’ in ‘Guthmann’ — and Rosa’s brother, Gustav Friedmann, were deported from Würzburg east to the Lublin area of occupied Poland. (In September 1942, Hedwig Friedmann was deported to Theresienstadt where her life ended in 1944. We do not know the fate of Berta Friedmann.)

The Yad Vashem website provides the following account of “25 April 1942 — The Third Deportation from Würzburg“:

“The Würzburg Gestapo ordered some 800 Jews from 19 different sub-districts and three different counties (a total of 80 different communities) to present themselves in Platz’schen-Garten, for the purpose of “evacuation”. On the 25th of April, 78 Jews from Würzburg were ordered to present themselves as well. At about 3:00 PM the deportation train left Würzburg, carrying 852 Jews. The train stopped at Bamberg to collect 103 Jews from the area, among them Jews from Nuremberg and Fürth, who had not been deported in the previous transport on the 23rd of March. On April the 28th the deportees reached Krasnystaw in the Lublin district of Poland.

Before boarding the transports, Jews were thoroughly searched for valuables hidden on their person or in their luggage, including weapons, foreign currency, money and jewelry. All items were carefully noted. According to documents of the German police, a total sum of 12,885 RM (Reichsmark) was confiscated from the Jews concentrated in Würzburg.

After the deportees reached Krasnystaw they were marched by foot to Krasniczin. The local Jews were murdered on the very day the Jews of Würzburg arrived. It seems that the surviving deportees were finally deported to Sobibor on the 6th of July, 1942.

This deportation of 852 Jews from Würzburg was documented by German policemen, and the photos were collected in an album for Michael Völkl, the Würzburg Gestapo officer charged with implementing the deportation.”

Auf deutsch sehen Sie Yad Vashem, Zugfahrten in den Untergang: Transport Zug Da 49 von Wuerzburg, Mainfranken, Bayern, Deutsches Reich nach Krasnystaw, Krasnystaw, Lublin, Polen am 25/04/1942.

*****

Our second question — why was Lothar Gutmann in Themar in the spring and summer of 1941? — may well never be answered.

Was Lothar in Themar voluntarily? Or was he forced to be in Themar or somewhere nearby to do involuntary labour for 6 months?

Perhaps the answer lies in files as yet unread in the Themar archives or in the Höchheim archives. Or perhaps someone reading this page can explain. If you do, or have any corrections or additions, please contact Sharon Meen @ s.meen79@gmail.com. We welcome your contribution.

*****

We owe a huge debt to Ms. Puth whose research allowed us to locate Lothar Guthmann within the context of his larger family.

For an outline of the families of which Lothar was a member, see Nachkommenliste.

Notes:

1. Hubertus Heule,,Zwei weitere Stolpersteine wider das Vergessen,” derweilen.de 19.08.2008.]

2. Brigitte Puth, ,,Sie haben auch Sara Else, Helene, und Lothar geheißen: Auf den Spuren der Familie Guthmann,” Attendorn — Gestern und Heute, Nr. 33, S. 3-22.

3. Puth’s research corrects the data published in the Bundesarchiv Gedenkbuch for the Teitel/Teytel family. See for example, entry for Helene Teytel.

4. Ancestry.com. UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 (database on-line). National Archives of Australia; Queen Victoria Terrace, Parkes ACT 2600. Inward passenger manifests for ships and aircraft arriving at Fremantle, Perth Airport and Western Australian outports from 1897-1963; Series Number: K 269; Reel Number: 88. See Jennifer Craig-Norton, “Polish Kinder and the Struggle for Identity,”in Hammel, Andrea; Lewkowicz, Bea, Kindertransport to Britain 1938/39 : New Perspectives, 2012, pp. 29-44.

5. Heike Schulte-Belle,,Australierin zu Gast in Artendorn,” WOLL, 05 Aug 2015.]

Zum Gedenken an die Opfer von Krieg und Gewalt: Thementafel: ,Die Verfolgung der Juden

Elfi Pracht-Jörns, Jüdisches Kulturerbe in Nordrhein-Westfalen – Reg.bez. Arnsberg, S. 459, cited in Aus der Geschichte der jüdischen Gemeinde: Attendorn.